At Petra’s “high place”

Jim had arranged for breakfast to be served half an hour early this morning so that the twenty of us who chose to follow him on a hike up to Petra’s “high place” to see the sunrise would not have to do so on empty stomachs. However, the evening staff with whom he had made the arrangements apparently failed to communicate that message to the morning staff, because they weren’t ready for us when we started gathering in the dining room at 6:00 a.m. Consequently, the sun was already up by the time we got on our way into the old city about 6:45. A guard at the entrance gate carefully checked the names on our two-day tickets against our picture IDs to make sure that we hadn’t bought them from scalpers.

Some members of our group chose not to participate in this morning’s hike—Emery and Mark’s parents among them—because Jim had warned us that it would be rigorous—as if yesterday’s expedition had not been. Reaching the ruined Nabataean temple on the high place involved climbing only six hundred steps, in contrast with the nine hundred we climbed yesterday to reach the panoramic view, but that would be only the beginning of today’s exertions—as you will learn.

Climbing to the “high place”

Today our guide was not Zaid, but Jim Gee, the tour’s general director. At this point, we probably should give you a fuller introduction to our illustrious leader (and also explain that Carol, his wife, is not with us because she is still in Utah, helping their daughter with the imminent birth of her first child). Jim isn’t merely an experienced tour guide who runs his own travel company; Jim is, quite simply, the Mormon Indiana Jones. We have no idea what his academic credentials are, but he seems to have been nearly everywhere and done nearly everything—and to have read nearly every book about the rest. (Nancy suspects that he is largely self-taught because of his idiosyncratic pronunciation of a lot of names.)

Trail to the “high place”

Jim says that he was inspired to begin studying old maps after learning that some ancient history scholars at Brigham Young University were trying to locate a spot on the Arabian Peninsula, mentioned in the Book of Mormon as the burial place of Ishmael (Lehi’s compatriot, not the son of Abraham), that had been called Nahom during the sixth century BC. Jim’s curiosity about Nahom became an obsession, and after a twenty-year search (during which he also became an avid antiquities collector) Jim finally found Nahom on an old map, right where he expected it to be. His expertise led to an invitation to participate in an archaeological dig, where, he says, he “learned on the job, from the best.” During the last fifteen years, he has continued to practice his digging skills. Although he has never been a professor, Jim—in addition to guiding several tours a year for Discovery Expeditions and Adventures—now participates an ongoing BYU dig in Petra.

As we walked through the narrow Siq (now for the third time) we noticed that the ground was wet, and little rivulets were running at the edges of the packed-dirt road. Jim said that although sometimes the road is sprayed to help keep the dust down, this looked like more water than usual. He surmised that run-off from the recent rains was finally making it out of the mountains and into the old city.

Aaron’s tomb way in the distance on top of Mt. Hor

Ruins of the temple at the high place

Jim in front of the ancient altar

Although we had missed the opportunity to watch the sun rise from the mountaintop, there was still plenty to see as a reward for our climb. We could look across the valley to a white stone monument on another mountaintop that marked the tomb of Aaron, the brother of Moses. There were two obelisks that delineated not only the location of the quarry where limestone for the temple had been cut, but also were set to mark the occasions when the moon and the planets were in alignment. When we got to the Nabataean temple, Jim pointed out the altar, and the basins where animals would be washed prior to sacrifice and the priest would clean his hands afterward. A large cistern nearby stored water. There are cisterns hewn out of solid rock all over Petra, mostly dry now, but formerly supplied by the elaborate system of water conduits we had seen yesterday.

Coming down from the high place

Lion carved into the side of the mountain

The stairs we descended on the back side of the mountain had once provided Nabataean royalty with private access to the temple complex, but today they gave us access to the king’s personal retreat. Jim pointed out the remnants of a huge stone lion carved into a wall, which once had been an impressive fountain with water flowing from the lion’s mouth. (The head had broken off in the earthquake; we had seen it in the museum in Amman.) An even more impressive former fountain became visible as we descended a steep switchback in the stairway: water had once flowed over an entire wall within a small courtyard that was hidden from view from both above and below. Next to the fountain wall was a fifteen-by-fifteen-foot chamber that included an observatory. Imagining the place in its original glory, the interior luxuriously furnished with carpets and cushions, and the fountain feeding abundant foliage and flowers, Michael decided that he wouldn’t mind living like the king of the Nabateaens.

Fountain wall

Observatory

Banquet hall

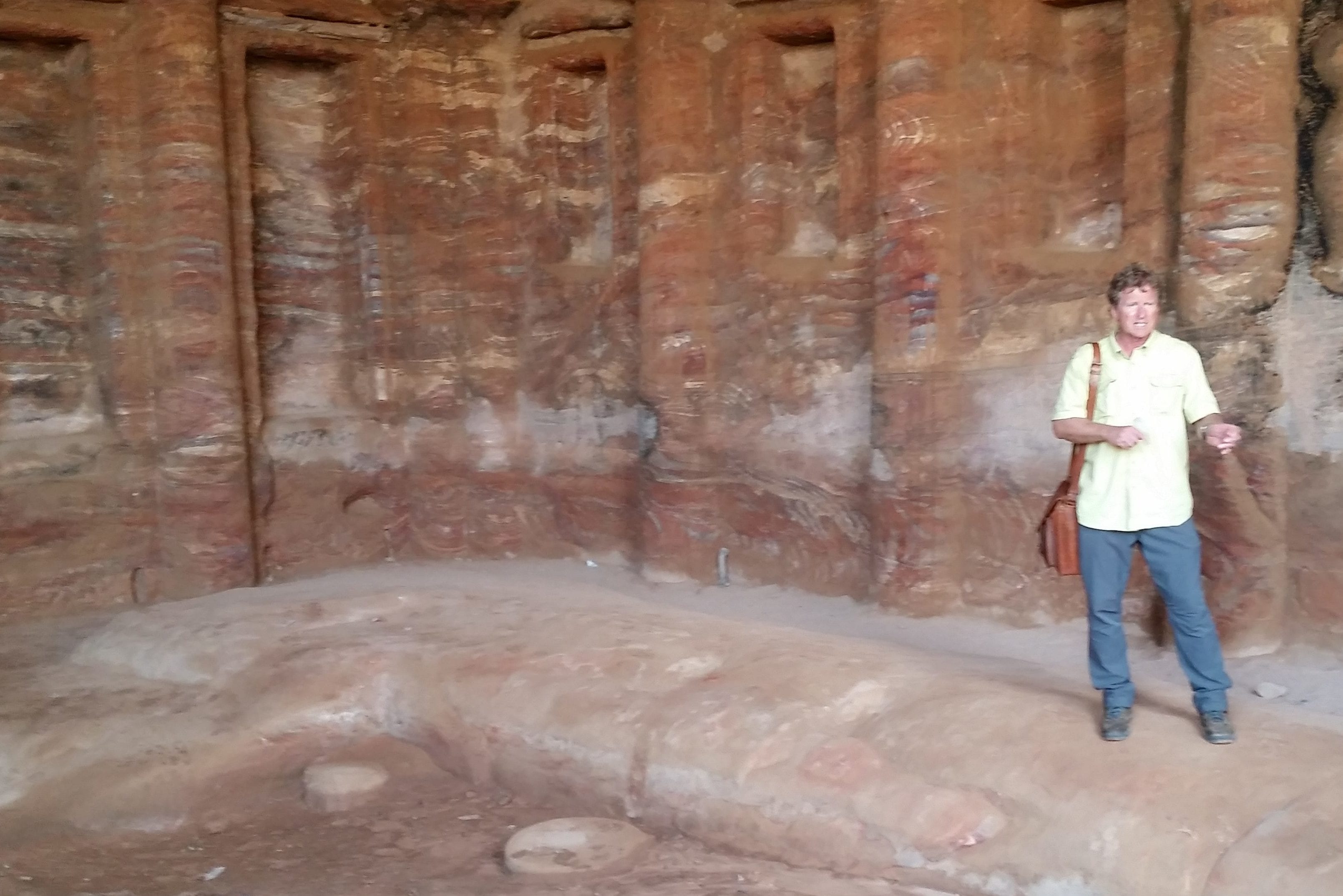

Triclinium inside the banquet hall

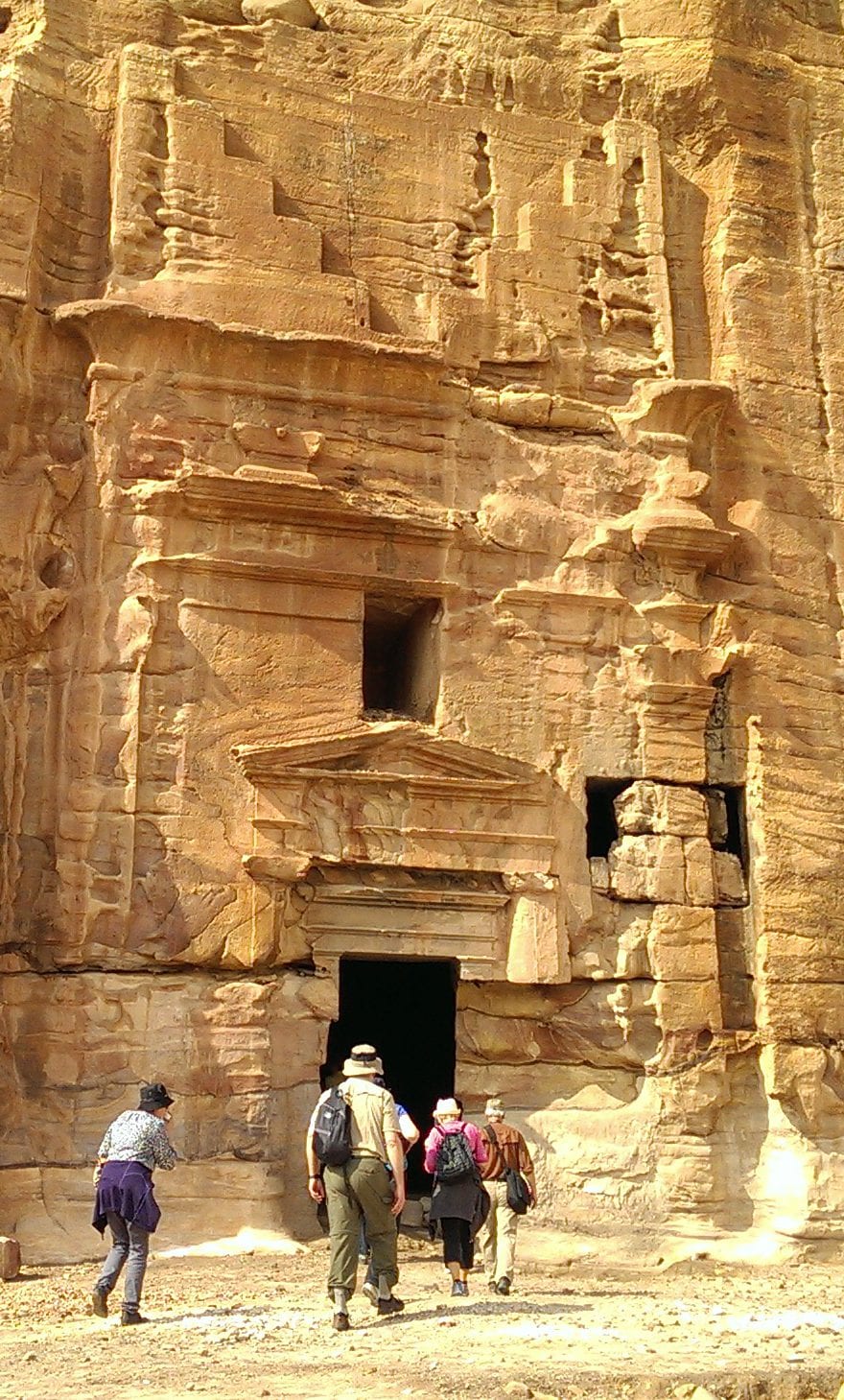

Soldier’s Tomb

Inside Soldier’s Tomb

At the foot of the mountain were the remains of the more public buildings of the royal compound. Although the main building is called the Soldier’s Tomb, Jim surmises that the “soldier” was actually King Aretas IV, and that the edifice called a “tomb” probably functioned more as a royal hall of justice. Across what was once a colonnaded square was a triclinium dining hall, which helped us envision the way the ancients were accustomed to eating: reclining, with one elbow resting on a low, U-shaped platform. Servants served the meal from within the U; other servants would have gone around the outside of the U to wash the diners’ feet as they ate. (Jim suggested that we picture a triclinium when we think of the Last Supper rather than the long banquet table Leonardo da Vinci and other Renaissance artists depicted.

Examining some very old coins

We stopped for a while outside the Soldier’s Tomb for a few members of the group who were interested in purchasing antiquities to examine some old coins offered by a Jordanian teenager who had followed us around all morning. Jim knew the girl, and offered assurances that her coins would be genuine, not knockoffs like those sold at most of the stalls we had passed yesterday. Jim had told us that with every rain, more coins, potshards, and other artifacts come washing out of the mountains. Local kids go out early to pick up the good stuff before the tourists start arriving, but it’s still possible to find pieces of pottery that are relatively intact. Once we started looking, we could see potshards everywhere. Jim said that since there are so many of them, no one cares if the tourists take a few home—so Nancy picked up some free souvenirs. Even though Petra is a World Heritage Site, security here is shockingly lax because the Jordanian government doesn’t have the money to provide much protection.

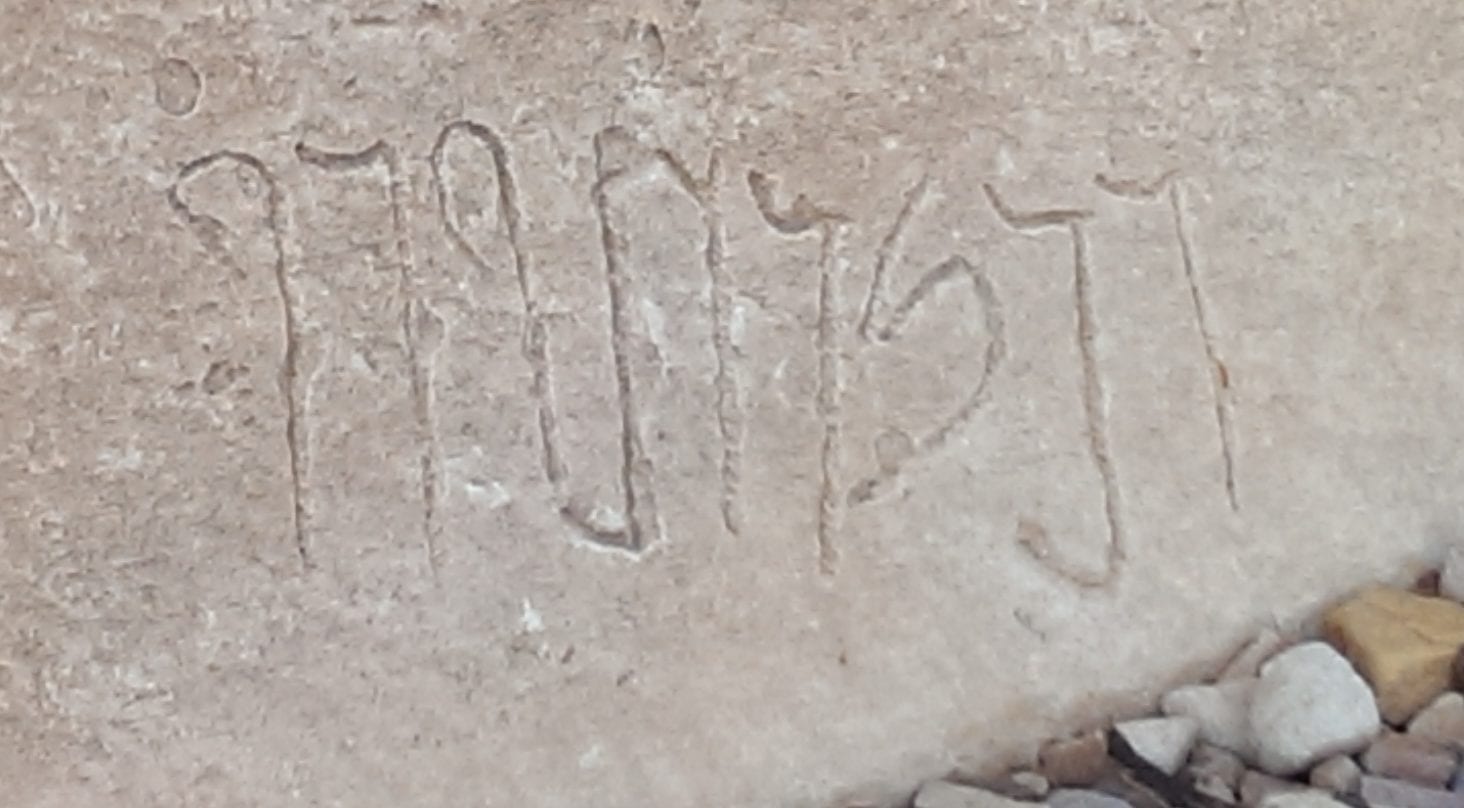

Nabataean inscription

Yesterday, Jim had explained that those who chose to go on this morning’s expedition rather than sleep in or walk into town to shop would be back to the hotel by about 11:30 a.m.—plenty of time, he assured us, to take a quick shower, pack our bags, eat lunch, and be ready to board the bus at 1:00 so we could go on to the Bedouin camp at Wadi Rum. It was now about 9:45 a.m. We were a little behind schedule, Jim told us, but if we did not dawdle, we still had time to hike to the site of Brigham Young University’s dig and return to the hotel in time for a shower. Rather than walk all the way back through the Siq, he said, we could take a shortcut through another narrow ravine that connected to an tunnel the Nabataeans had constructed to divert rain water away from the center of town.

Goats freely roam the mountains of Petra

“I’m sure by now you know your way back through the Siq,” Jim said, “so if anybody wants to skip the BYU dig and head back to the hotel, go ahead.”

Nobody turned back, so the group quite literally left the beaten path and struck off across the barren hills of Petra.

Nancy’s boots

Before we continue with our narrative, Nancy would like to take a moment to express gratitude for her beloved Merrell Moab hiking boots. They have carried her across deserts, over mountains, through muddy waters, up ancient stone stairways and down modern city streets on four continents with nary a blister. And man, did she need them today!

Brigham Young University is one of only four or five organizations authorized to dig at Petra. Their assigned site covers several acres, about a mile from the center of Petra. The area includes a number of tombs, most of which are simply natural caves—the type that would have been utilized by Nabataean commoners rather than the nobility. (Indeed, some of them are currently in use as homes by local squatters; we saw many caves filled with simple furnishings, some outfitted with electric lights, appliances, and satellite dishes powered by small generators.) However, at least one of the tombs in BYU’s territory is a monumental one, not as large and imposing as those we had already visited, but no less fascinating—especially after Jim told us what he had found there a few years ago.

BYU’s archaeological “concession”

Active digging goes on only for a few months each spring, so all equipment has been removed, and except for us, the site was completely deserted.

There are six separate burial sites within the larger chamber. Jim explained that, like nearly all ancient tombs, most of these had been robbed centuries ago, usually soon after the burial by relatives who knew where they were and what had been placed inside. Before the BYU team could get to anything significant, they had to remove a layer of dirt, debris, and dung (animals use these caves, too) that was several feet deep. When they uncovered the tombs themselves, the archaeologists could see that most of the stone lids had been smashed where the head and feet of each body would have been placed—typical damage, Jim explained, because intruders knew that most of the precious articles would have been placed there, and the robbers wanted to get at their booty with as little effort as possible. The lid of one of the tombs, however, had only one crack across the middle; Jim decided to start excavating that one.

He and a student assistant levered up and removed the pieces of the heavy stone lid and then began the slow process of carefully removing and sifting through the dust that had accumulated inside. Human bones began to appear. Then, brushing away some loose dirt near the skull, they caught the glint of something shiny.

“Gold!” cried the student.

Jim quickly hushed her to avoid alerting the local hired hands. He continued brushing with growing excitement to reveal a golden medallion covered with Nabataean script.

Leaving his assistant to stand guard, Jim stood up and sauntered nonchalantly out to where David Johnson, the dig director, was working. In his most casual voice, he said, “When you have a minute, come inside so I can show you something.”

Dr. Johnson, who could read Nabataean, examined the medallion for a few minutes and then said, “It’s a curse! No wonder the grave robbers put the lid back on it and left it alone!”

A cistern still under excavation

The skeleton belonged to a woman who had been about forty years old. Near her feet, Jim found a plaque bearing her family name. It had been broken in half, not by robbers, but before burial.

“Clearly,” he explained, “this woman had done something terrible to disgrace her family and bring upon herself such a curse,” but at this point no one knows what that might have been.

The administrators of the Petra National Trust were excited to learn of the discovery at BYU’s dig and enthusiastically adopted the same nickname that Jim’s team had begun calling the site: the “Tomb of the Golden Curse.” It will be several years before the archaeologists are ready to open it to the public, but it’s likely that this site will become a popular tourist attraction. I mean, wouldn’t you want to see the Tomb of the Golden Curse?

By the time Jim had finished his story, it was after 11:00, but if we hurried, the shortcut through the water diversion tunnel should get us back to the hotel by noon. We picked our way back down the hill toward the ravine that led into the tunnel. When they saw us headed in that direction, a couple of local girls called out a warning that we should go back the way we came, but Jim didn’t seem worried.

“They just don’t want us to get lost,” he said. “The ravine isn’t very wide, and it probably will be muddy after all that rain, but I’ve been through there many times and we shouldn’t have any problems. Besides, we don’t really have time to walk all the way back around the way we came.” So, walking in single file, we followed our fearless leader into the narrow pass.

Reaching an impasse through the “shortcut”

Almost immediately, we encountered patches of very slippery mud. In some places the mud was so deep that some people were in danger of losing their shoes. In other places, there were big puddles to either climb around or plunge through. Several people had to slide down a muddy incline on their bottoms. Whether a pile of old tires had been wedged into the ravine to help or hinder us we weren’t sure, but whatever the case, we climbed over them. Keep in mind that the floor of this ravine was not flat. Where there was no mud or standing water, there were rough rocks to scramble over. Like a business group engaged in a team-building activity, we helped each other navigate the increasingly treacherous terrain, trusting that the ravine was taking us closer to the nice, warm showers back at the hotel.

Then those of us who were farther back in the pack heard Jim’s voice echoing through the ravine.

“Hold up! There’s deep water ahead,” he said.

“How deep?” someone called.

“Thigh-high. Maybe more. It’s hard to tell.”

Those of us who had just managed to clamber over a particularly rough barrier stopped and stared at each other. Nobody was eager to forge on through thigh-high water, but neither was anyone very keen on retracing our steps—especially since we knew that if we turned around, we would face the whole five-mile hike back through the center of Petra. We were tired. We were hot. We were thirsty. And we were stuck.

Finally, Jim made the executive decision: “Since we can’t be sure what we might find ahead, we’d better go back.”

Anne and Mark T were the first to make it back to the hotel, where a very worried Emery was waiting on the terrace. She had expected the group to return almost two hours earlier.

Mark wearily pointed at her and said, “You made the right decision!”

Mark “hoofing” it back to the hotel

Lynn hitching a ride back

Michael and Nancy dragged into the hotel about ten minutes later. Since it was just after 1:00, the time we were scheduled to leave Petra, we hurried upstairs to finish packing our bags and came back to the bus without having showered or changed clothes. Hani, our driver, was not too happy to see mud caked all over the seat of Nancy’s pants and asked her to change, but since her cleaner pants were in a suitcase that had already been locked under the bus, there wasn’t much she could do. She brushed herself off as well as she could and waited to board until Hani was looking the other way. Had we known that some people had taken time to shower before they came downstairs, we would have done the same, but by the time we figured that out, it was too late. Not only were we dirty, but we were famished. Fortunately, we had made ourselves pita sandwiches from the breakfast buffet; others who had not similarly prepared had to ride to Wadi Rum on empty, rumbling stomachs.

Michael checked his Fitbit after we got on the bus. The tally: more than 15,000 steps, 9.4 miles, 123 flights of stairs. And the day was only half over.

Leave A Comment