Throughout the Commonwealth of Nations—countries that formerly were part of the British Empire—1 June is celebrated as the Queen’s Birthday (despite the fact that the Queen’s actual birthday has been 21 April for at least the last 62 years). What this means for New Zealanders is that 1 June is a national holiday, and because this year 1 June fell on a Monday, everyone could look forward to a long holiday weekend. The staff of the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre gets Mondays off every week, so Elder G declared that we would take Saturday 30 May as our Queen’s Birthday holiday. Even though at that point the New Zealand government was allowing slightly larger public gatherings than had been allowed the previous week (now up to fifty), regular meetings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were still suspended, so the MCPCHC staff was looking at a real three-day weekend: our last days of unstructured time before we had to reopen the museum and go back to our pre-lockdown work schedule. Barry suggested that we take advantage of the opportunity and take a three-day excursion to Paihia and the Bay of Islands.

Throughout the Commonwealth of Nations—countries that formerly were part of the British Empire—1 June is celebrated as the Queen’s Birthday (despite the fact that the Queen’s actual birthday has been 21 April for at least the last 62 years). What this means for New Zealanders is that 1 June is a national holiday, and because this year 1 June fell on a Monday, everyone could look forward to a long holiday weekend. The staff of the Matthew Cowley Pacific Church History Centre gets Mondays off every week, so Elder G declared that we would take Saturday 30 May as our Queen’s Birthday holiday. Even though at that point the New Zealand government was allowing slightly larger public gatherings than had been allowed the previous week (now up to fifty), regular meetings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were still suspended, so the MCPCHC staff was looking at a real three-day weekend: our last days of unstructured time before we had to reopen the museum and go back to our pre-lockdown work schedule. Barry suggested that we take advantage of the opportunity and take a three-day excursion to Paihia and the Bay of Islands.

Michael and Nancy had visited Paihia and the Bay of Islands with Michael’s sister during our tour of New Zealand in 2014, but this was a very different trip from that one (which, if you’re interested, you can read about here). A major difference between the two was that in 2014 we had visited in midsummer; this year we visited in late autumn—the beginning of the rainy season. Another major difference was that this year, with New Zealand’s borders closed to international visitors, there were no big cruise ships in the bay and not nearly as many other tourists wandering around town.

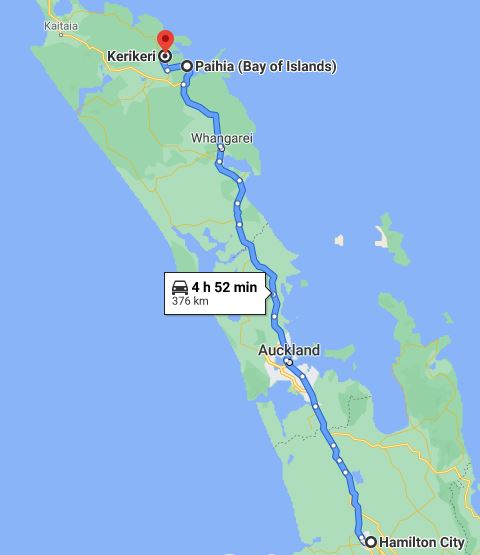

We closed the MCPCHC’s office shortly after noon on Friday 29 May and started driving north. In addition to Elder and Sister G, our travel group included Sister E. We decided that five people with luggage would not fit comfortably enough in one Toyota Corolla for a five-hour drive, so Diane rode with Barry and Eva, and we drove separately. We had expected to encounter heavy traffic in Auckland, but were relieved that we were able to whiz right through. Rain fell intermittently.

800-year-old McKinney kauri tree

600-year-old Simpson kauri tree

Old trailer used to haul cut kauri trees

Kauri saplings for sale in the museum shop

On the way to the bay, we stopped in Warkworth to visit the Parry Kauri Park, about 60 km north of Auckland. The park consists of walking trails through many acres of bush, and features two giant kauri trees. The larger of the two, named “McKinney” after Warkworth’s first Presbyterian minister, measures 25 feet around at its base and is 125 feet tall. Although it is over 800 years old, it is merely an adolescent by kauri standards. The second tree, about 600 years old, is named “Simpson” for the family who bought the land after Reverend McKinney’s death in 1905. Although the Simpsons harvested many of the trees on the property, they recognized that the oldest, largest kauri trees were becoming exceedingly rare, so they made provisions for their land to eventually become a nature preserve. Parry Park is named for one of the men who helped raise the money to purchase the property from the Simpson estate and establish a public preserve. The park also includes the Warkworth Museum. It had closed just before we arrived, but we were able to see some outdoor displays of hundred-year-old logging equipment and tools for “gum digging.” “Gum” is fossilized kauri resin—similar to amber—which was used in jewelry and varnishes.

We had been warned

The rain abated as we continued north on Route 1, but we ran into a traffic slowdown that ended up adding more than an hour to our trip. Nancy used the time to compose overdue email messages on her phone as Michael tried to avoid fuming behind the wheel. We never did determine exactly what had caused the tie-up, but because things started to move after 5 p.m., we surmised that it was due to road construction too far up the highway and over too many hills for us to see.

One very long queue

Dramatic sunset

Michael found the hills especially disconcerting because they had been missing from his mental image of our previous drive to Paihia. In his memory, the terrain around Whangarei (158 km north of Auckland) was flat, but in reality it is anything but. Even prettier than the hilly terrain was the sky, which became increasingly dramatic as the sun went down behind clouds gathering on the horizon. We weren’t sure what weather to expect for the rest of the weekend because the forecasts shifted as often as the cloud formations.

Busby Manor Waterfront Resort, Paihia

Interior of Green’s

All of us were happy to finally arrive at the Busby Manor Waterfront Resort in Paihia. We shared a suite with a fabulous view of the bay with Barry and Eva; Diane got her own room just underneath us. By the time we checked in and unloaded the luggage, it was close to 7:00 p.m. and all of us were eager for dinner. Barry and Eva suggested that we go to Green’s, which happened to be the same place we had eaten in Paihia six years ago. Since then, however, the restaurant has moved to a larger location down the street. Green’s offers two complete menus: one with Thai food and the other with Indian. That night we decided to order Thai, pledging to come back for Indian another time because the Tom Yum soup and Thai curries were so good. After dinner, the weather was pleasant enough to entice us to walk down the street for ice cream at Møvenpick, a Swiss chain with several locations in New Zealand. Back at Busby Manor, the five of us played a round of Five Crowns before retiring.

Saturday morning sunrise from our balcony

Eva and Barry walk along the beach

Rain started beating against our windows soon after we went to bed, so we feared that we were in for a gloomy, wet Saturday. We were thrilled, however, when we drew open the curtains Saturday morning just in time to watch the sun begin to rise above a few wispy, golden clouds. After a quick breakfast of cereal we had brought from home, we all took a leisurely walk along the beach. We went about 5km, almost as far as the Waitangi Treaty Grounds, where New Zealand began its life as a unified nation in 1840. We looked forward to visiting the treaty grounds and the adjacent Waitangi Museum the next day.

Makana Confections Chocolate Factory

Making chocolate-dipped cookies

After our morning stroll, we drove up to Kerikeri, planning to visit the farmer’s market. However, the siren scent of chocolate emanating from the Makana Confections Boutique and Factory across the street from the market was irresistible, so we went there first. We watched as confectioners dipped cookies and drizzled truffles with a delicate chocolate coating, then eagerly accepted samples of chocolate-coated macadamia nut toffee. The tasty tidbits tempted us to buy a box to take home, but the astronomical prices soon drove the thought from our minds.

Kerikeri Farmers’ Market

Kauri Workshop

The contrast between the tidy, sterile environment of the chocolate factory and the shaving-strewn disorder of the woodworking shop was not lost on us

When we crossed the street to the farmer’s market, we discovered that getting beyond the gate would require standing in line until enough other Saturday morning visitors finished their shopping and left, because stores were still prohibited from admitting more than 99 people at a time. We decided to forgo the 45-minute wait and instead went into the Kauri Workshop, next to the chocolate factory. Here we could browse among all manner of items fashioned from kauri wood: everything from carved and inlaid artworks to simple wooden spoons. A window at the back of the store gave us a peek into the woodcarvers’ workshop, but unfortunately no one was working there that day.

Diane and Michael wash hands before entering the self-service avocado stand

On our way back to Paihia later that morning, we pulled off the road at a help-yourself farm stand offering three varieties of avocados, priced according to quality and size. We bought five large fruits from the $2-per-piece bin; payment was on the honor system, cash only. After we got back in the car, we learned that Barry and Eva had owned an avocado orchard when they lived in southern California. They hadn’t really intended to be avocado farmers, but the grove had come with the house they wanted to buy. At the time of purchase, they told us, the trees looked completely dead, but their realtor had said that all they needed was water. The realtor was right. Once they started irrigating, the trees revived and started to produce so many avocados that Barry and Eva had to contract with an orchardist to harvest and market them.

After stopping for the avocados, we had to hurry to get back to Paihia by noon. We didn’t want to be late for a lunch appointment that Diane had arranged for us.

One of the reasons Diane had wanted to join our expedition to Paihia was so that she could meet a couple who were friends of one of her friends from the States. The rest of us were interested in meeting this couple as well, because they held the keys—literally—to a historic building that had been one of the first chapels of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Northland (the district comprising everything north of Auckland). Erected by the Going family in 1940 and then donated to the Church, the little chapel had reverted to the family when the Church built a standard meetinghouse for the community thirty years later. Barry and Eva had planned to take us to see the Goings’ chapel during our trip north, so they were delighted to learn that Diane had a way to contact someone from the family who could let us inside.

Percy and Gertrude Going were two of the few Pākehā (Europeans) who joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New Zealand during the nineteenth century and did not emigrate to Utah. Percy’s parents were from Essex, England, and had brought their family to New Zealand in 1859, about nine years before Percy was born, and eventually established a farm in Kamo (just north of Whangarei). Gertrude’s parents also had emigrated from England. In their youth, Percy loved to play cricket while Gertrude and her friends loved to watch cricket matches, so it was on a cricket field that the two of them met.

After they were married in 1890, Percy’s father gave the couple a piece of land adjoining his, plus two heifers to start their own dairy herd. One day a few years later, while Percy was working in his hay field, two missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints showed up, took off their jackets, and started to help him. Percy’s older sister Laura and her husband, Tom, had joined the Church in 1889, so Percy and Gertude were motivated to learn more. After some study and heartfelt prayer, and following the promptings of the spirit, they decided to be baptized.

Unlike Laura and Tom, however, Percy and Gertrude did not join the Latter-day Saint migration to America. About 1910, Percy and Gertrude sold their land in Kamo and moved to a bigger farm in Maromaku, about 45 kilometres away. After milking cows by hand since childhood, Percy became one of the first farmers in New Zealand to employ milking machines. Despite working very hard on the farm, the Goings always made time for participation in the Church, hosting Sunday services in their home. As the membership of the Maromaku Branch grew, Matthew Cowley, president of the New Zealand Mission, decided that the little community of Maromaku deserved its own meetinghouse. By the time President Cowley got approval from Church headquarters in Salt Lake City to erect one, however, the Going family not only had donated the land for it, but also had constructed a sturdy little chapel with wood from a single giant kauri tree that had been growing on their property. Unfortunately, neither Percy nor Gertrude lived to see the building completed, but they left nearly a dozen children and many grandchildren to carry on their legacy of faith in Jesus Christ and commitment to his restored church.

One of those children was Cyril, born in 1898. When the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints opened its Māori Agricultural College near Hastings in 1913, Cyril became one of its first students—even though the school’s prospectus had stated that it would admit neither girls nor Pākehā boys. But the MAC’s primary purpose was to provide an education for boys from remote villages who had little opportunity for furthering their education, and because that precisely described the Goings’ situation, Cyril was allowed to matriculate.

When he completed his course of study, Cyril returned to Northland, worked in the family dairy business, and got married. His wife Margaret gave birth to seven children before her premature death in 1935. While she was sick, Cyril hired a young Māori woman named Mary Grace Paki to help his wife with household chores and childcare. When Margaret died, Cyril asked Mary to stay on; she agreed to do so only until he could find someone else to look after the family. When, after two years, Cyril still had not found someone to take her place, Mary asked what his intentions were. He responded that he intended to ask her to marry him—which she did. Mary proceeded to add six more children to the family; one of them was a son named Sidney, born in 1943.

By the time Sid was old enough for secondary education, his father’s alma mater no longer existed. An earthquake in 1931 had destroyed most of the MAC’s buildings and, because the institution had never achieved financial stability, Church leaders had decided not to rebuild it. However, in 1958 the Church opened a new secondary boarding school in Hamilton—the Church College of New Zealand—so that’s where Sid went.

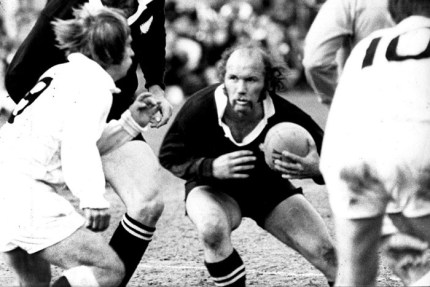

Sid Going in his heyday

After graduating from CCNZ, Sid went to Canada to serve a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, something his father had not been able to do. When Sid returned, he attended Northland College and resumed work in the family business, but what he really loved—and excelled at—was rugby. Sid quickly became a star of the provincial North Auckland rugby union team, for which he played from 1965 to 1978, often alongside a couple of his brothers. In addition, “Super Sid,” as he was called by fans, played 86 matches with the All Blacks, New Zealand’s national team, between 1967-1977—about a third of them against international clubs. And thanks to his mother, Sid also qualified to play for the New Zealand Māori team. Still considered New Zealand’s greatest running halfback, Sid was appointed a Member of the Order of the British Empire for “services to rugby” in 1977, and inducted into the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame earlier this year.

Barry, Sid, Diane and Michael enjoy the view of the bay from the Goings’ porch

After retiring from first-class rugby, Sid returned to Maromaku and took over the family dairy business, although he continued to coach rugby at the secondary-school level, and later participated in selecting players for the national All Star team. We were intrigued to learn that although we might think of Sid as a “professional” rugby player, none of the teams he played for offered a salary (even the All Blacks did not go pro until 1995), and players often had to raise their own funds to help cover travel and other expenses. Eventually, Sid sold his portion of the dairy business and turned it over to one of his sons. Another of his sons became an architect, who designed a beautiful home for Sid and his wife, Colleen, to enjoy once they fully retired. The house is located on a bluff in Paihia, overlooking the Bay of Islands, and on that gorgeous Saturday just before the Queen’s Birthday, we were headed there for lunch—thanks to Diane’s connection to the Goings through a mutual friend.

Diane with Colleen and Sid

Considering what “Super Sid” Going means to sports fans in New Zealand, this was the equivalent of being invited to lunch by Walter Payton or Roger Staubach—except that neither Payton nor Staubach had also been the bishop of an LDS ward, nor the president of the Hamilton New Zealand Temple. And we doubt that they could have been more gracious hosts. Sid entertained us with stories about rugby, church service, and his family, while Colleen served a delicious meal featuring an assortment of salads, homemade berry muffins, and hot-off-the-griddle corn-and-broccoli fritters. As we took in the spectacular view from the balcony after lunch, Colleen pointed out a couple of their grandchildren floating on a paddleboard near the shore below, and told us that she likes nothing better than taking her own little boat out on the bay to catch a few fish for dinner. Warm and totally unassuming, the Goings made us feel as though they considered it a privilege to have us in their home, rather than having granted us the privilege of being there. We had a marvelous time.

Sid and Colleen had been to the farm in Maromaku earlier in the week to help their children with the calving. They had other plans for Monday, when we planned to visit Maromaku, but they made arrangements for someone else to meet us at the Goings’ historic chapel that morning and let us in.

The Paihia-Russell Ferry

After we said our thank-yous and goodbyes, we hopped on the ferry that took us across the bay to Russell, which had been the first permanent European settlement in New Zealand. Māori had lived at the site for centuries, enjoying the peninsula’s pleasant climate, fertile soil, and abundant fish. They called their village Kororāreka. According to legend, the name is derived from a statement made by a Māori chief who had been wounded in battle, after he was revived by broth made from a little blue penguin. He is believed to have said, “Ka reka te kororā” (how sweet is penguin). We spotted a few little blue penguins in the bay, and were told that they sometimes come ashore at Russell/Kororāreka after dark to nest under the floorboards of waterfront buildings.

Approaching Russell

Although Kororāreka had not been an important Māori settlement until Europeans arrived in the early nineteenth century, local Māori helped transform the town Pākehā called Russell into a thriving seaport, and briefly, New Zealand’s first colonial capital. For many years, Russell was a vital resupply center for whaling and sealing ships plying the South Pacific. With commercial growth came the evils common to many port cities, however: drunkenness, gambling, prostitution, and general lawlessness. Russell’s reputation as the “Hell Hole of the Pacific” cost the town its position as capital after 1840, when the colonial governor decided to find a more dignified location for the seat of government and moved to Auckland.

Eva and Barry walk toward the Duke of Marlborough Hotel, which relishes its reputation for “refreshing rascals and reprobates since 1827”

The lounge inside the Duke of Marlborough Hotel, which was granted the first liquor license in New Zealand (not that it mattered to us)

Christ Church, the oldest church in New Zealand

Today, Russell is a quaint historic village with around 800 permanent residents. The town survives by attracting tourists to the hotels, restaurants, and boutiques lined up along the Strand. We peeked into the elegant Duke of Marlborough Hotel, opened in 1827 and now restored to Victorian-era grandeur, but Barry directed us to one of Russell’s quieter attractions: Christ Church, the oldest church in all of New Zealand. Built in 1835, it may also be the oldest structure in the country still used for its original purpose. When Christian missionaries purchased land for the church from Kororāreka’s Māori chiefs, they agreed that the cemetery should be open to both Pākehā and Māori. We enjoyed wandering among the gravestones, reading the names and speculating on the lives of the people they represented. Another interesting tidbit of information about Christ Church: listed among the subscribers who contributed funds to build it in the 1830s are “Captain Fitzroy, Mr. Charles Darwin and officers of HMS Beagle.”

Russell Town Hall

This memorial honors the fallen from several wars. One of its plaques reads: “Commemorating the past with the new with thanks to those who gave so that we can live the bountiful life we lead”

Tamati Waka Nene Reserve

Russell is also the site of the Tamati Waka Nene Reserve, which honors a prominent Māori chief who signed the Waitangi Treaty and promoted the agreement among his own people. Respected as a wise negotiator and peacemaker, he lived on this site in Russell during his later years.

Diane, Barry, Michael, and Eva near the Russell marina

A boat returning from a fishing excursion

Fishermen on one boat had caught a couple of good-sized kingfish

Although it is possible to reach Russell from Paihia by car, most people take the fifteen-minute ferry ride because the tortuous road trip requires more than an hour and a half. On the fine holiday-weekend Saturday when we visited, however, we might have been just as well off driving, because there were more tourists than the scheduled ferries could handle. Not wanting to be left stranded in the Hell Hole of the Pacific before nightfall, we cut our visit short and stood in line for over an hour for the ferry back to Paihia. Fortunately, it was a pleasant evening, and it was fun to watch the sport-fishing boats come in and unload their catches.

Diane, Eva, Barry, Michael and Nancy around the table at JFC

Guillotine board game

Another reason we left Russell early was that watching the fishermen had given us an appetite for seafood, but we had not made a dinner reservation and none of the restaurants in Russell had any tables available. As we soon discovered, there weren’t many tables available back in Paihia, either. For a town known as a tourist destination, Paihia doesn’t have a lot of restaurants, but TripAdvisor told us about a new one very near Busby Manor, where we were staying: JFC (Just Fish & Chips). It sounded like just what we were looking for—especially because they could seat us right away. What TripAdvisor had not warned us about was that getting a table and having our order taken quickly did not necessarily mean that our food would arrive just as speedily. We waited ,,, and waited … and waited … and waited … until we began to wonder whether the chef had not shown up or something. When the server finally brought our order, it was hard to tell whether the food was really good or whether we were just so happy to get it that anything would have satisfied us, but we think it actually was quite good. The seafood chowder was full of all kinds of interesting shellfish, and both the lightly battered snapper and the chips were nice and crispy and very fresh. All of us had ordered the “JFC Meal,” which included a starter, and an ice cream novelty that we could choose out of the freezer case. Most of us chose Magnum bars, which we took back to the hotel and ate while we set up a game of Guillotine.

On our way to the restaurant earlier in the evening, we had noticed that the lights were on in the lovely old stone church next to Busby Manor. Saturday night mass was due to begin in about twenty minutes, so we were able to go in while they were setting up. St. Paul’s Church is shared by both Anglican and Catholic congregations; this service was to be a Catholic one. Those who had arrived early welcomed us graciously and allowed us to take a photo of the beautiful interior.

St. Paul’s Church, Paihia

What a great getaway for you all. We have to let our NZ friends know about Super Sid – they will be jealous!

What an awesome 3 day adventure for you all!!! You both look wonderful and SO happy!!! Enjoy so much all of your posts. Keep them coming!!! Love you both.