The Oasis Buffet at breakfast time

After so many days when we had to rise early for a game drive or to leave on a long trip to our next destination, our internal clocks woke us up before dawn this morning even though we could have slept in. We took some extra time to luxuriate in the shower (where, initially, the water was dangerously hot) and extra time at the breakfast buffet (where the freshly made crepes were deliciously hot). We needed some extra time after that to securely pack all our stuff for tonight’s flight home, because although we would be spending the whole day in Nairobi, once we left the hotel this morning we would not return.

Today our group was met by only four Discovery XA drivers, Anthony and Steven having left to fulfill assignments with another tour company. Even though that meant that each of our Land Cruisers now had a capacity load of six passengers, it wasn’t a problem because we wouldn’t be spending too much time on the road today. We were in Amos’s vehicle again, joined by Barry, Eva, Steve, and Jan. Because one of the seats in the back was wobbly, Michael sat up front with Amos once more, enjoying the view and the driver’s commentary as we drove through the city.

Jamia Mosque Nairobi

Traveling south on the eight-lane Uhuru Highway, the main route through central Nairobi, we passed the Nairobi National Museum, the University of Nairobi, and a roundabout that Amos calls “the Holy Triangle” because it is the site of St. Paul’s Catholic Chapel, the Lutheran Church of Kenya, and the Hebrew Congregation of Nairobi. Only a few blocks away, we could see the silver domes and minarets of Jamia Mosque Nairobi, Kenya’s most prominent Islamic site, reaching into the sky.

The Kenyan flag

A mile or so beyond the roundabout, we turned west onto Langata Road and passed the Uhuru Gardens, a memorial park where in 1963 the British flag was lowered and the Kenyan flag raised to officially mark Kenya’s transition to independence.

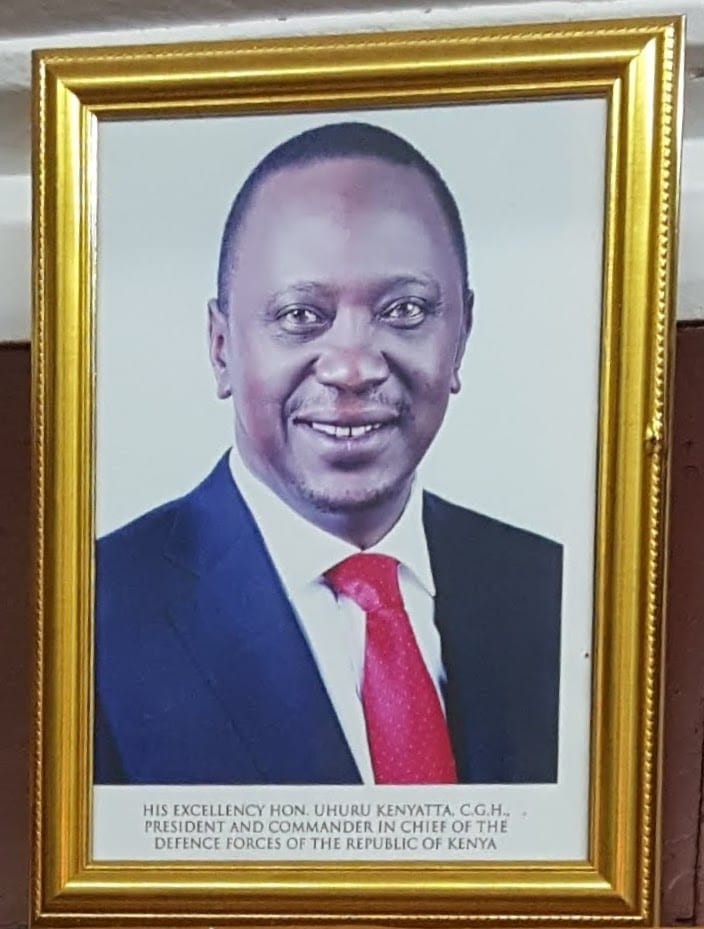

Nearly every establishment we visited displayed a photo of President Uhuru Kenyatta

Uhuru is Swahili for freedom, and is the name not only of the highway and the gardens, but also of Kenya’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta. His father, Jomo Kenyatta, had been a notable proponent of African nationalism during the 1940s and 50s. Jailed in 1952 on false charges of fomenting a violent anti-colonial rebellion, eventually he was released and led Kenya’s peaceful transition to independent rule by successfully gaining support from native tribal leaders as well as many white settlers. During his tenure as president, Jomo Kenyatta was criticized for allowing his own Kikuyu tribe to dominate the country’s leadership, and his successor, Daniel arap Moi, became infamous for financial mismanagement, corruption, and human rights abuses. Kenya’s third president, Mwai Kibaki, was known as a technocrat who had no interest in developing the same type of personality cult that both his predecessors had enjoyed. Kibaki succeeded in getting the economy onto a more secure footing while providing free education for all primary school children, although he, too, was accused of favoring the Kikuyu elite. Uhuru Kenyatta was elected president in 2013. According to Amos, he is popular because “he is a man of the people,” but our driver is not convinced that those around him are as trustworthy.

About four miles southwest of the downtown area we came to Nairobi National Park, established in 1945 as Kenya’s first state-sponsored wildlife preserve. It covers more than 45 square miles–which sounds huge, but actually is rather modest by African national-park standards. Within its electric fence, city visitors can experience a mini-safari that includes zebras, giraffes, wildebeests, gazelles, rhinos, and lions–but no elephants, because the park isn’t big enough to support the elephantine appetite of a whole herd.

Welcome to the elephant and rhino refuge

However, one can see a lot of baby elephants at the elephant and rhinoceros nursery operated in a corner of the park by the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. Founded in 1977, the DSWT rescues orphaned elephants and rhinos from other parts of Kenya and brings them here for nurturing and rehabilitation before reintroducing them into the wild. This orphanage was our first destination for the day.

Knowing that Monday-morning traffic in Nairobi was likely to be as heavy as last night’s Sunday-evening traffic, Jim had allowed more time than we needed to get across the city so we wouldn’t miss the DSWT Nursery’s short visiting period. Thus we had a long wait outside the gate before it finally swung open at 11:00 a.m.–but we were glad to have arrived early as more and more other tourists began crowding into the queue behind us. We struck up a conversation with a neighboring group, five attractive young women who turned out to be flight attendants for Emirates Airlines. Although they were conversing with each other in English, none was a native English speaker: they hailed from Germany, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, and Morocco. The Polish woman was easiest for us to understand because she had lived in Canada for several years as a child, but later returned to Poland to attend college. She explained that she and her colleagues were enjoying a day of sightseeing before having to report for duty later tonight.

Visitors gathered around the feeding area, waiting for the elephants to arrive

Having been among the first in line, we were able to secure prime viewing spots next to a large roped-off area where the youngest elephant calves soon were ushered out for their late-morning bottles. (“Elevenses,” you could call it–apparently they follow the same feeding schedule as hobbits, every three hours.) We were surprised to learn that their bottles are filled with human baby formula, which–after much frustrating trial and error–was determined to contain the right concentration of nutrients for infant elephants. (Cow milk has too much fat.)

Each elephant calf is allowed two 1.5-liter bottles per feeding–although a few tried to sneak more

This “toddler” is about three years old and likes to hold her own bottle. Elephants do not reach maturity until they are about fifteen

Older calves supplement their infant formula with foliage

We were allowed to touch the elephants if they came close enough to the rope for us to reach them. Their skin is very rough, sparsely covered with stiff hairs

Wallowing in mud is not only fun, but useful: the mud coating helps protect elephants from sunburn and insect bites

If you look closely, you can see where this elephant’s trunk was stitched back together after she tore it trying to escape from a snare. She kept picking out the sutures, however, so the hole will probably remain open after the wound heals

We watched the little elephants gulp down the contents of their bottles and then cavort in the mudhole, the docent explained why each was brought to the DSWT Nursery. Not every young elephant orphaned in the wild needs human intervention to survive, but the twenty calves currently in the orphanage all have experienced severe trauma as a result either of drought, or of what the guides call “human–wildlife conflict.” Such conflict ranges from the overt to the unintentional: one rescued calf took a poacher’s bullet in the knee; another severed her trunk when it got caught in a hunter’s snare; one was found at the bottom of a well. The old adage that “an elephant never forgets” happens to be a true one, so animals that have suffered horrific experiences may display the same kinds of PTSD symptoms as humans. Elephant keepers on the DSWT staff are assigned to work with specific individuals, taking on the role of the orphan’s “family” as they work to heal them both physically and emotionally.

This calf enjoyed straddling the water trough. Many orphans brought to the nursery have lost their mothers as a result of drought

One of the calves we saw today arrived only three days ago, severely dehydrated. Most rescued elephants who come to the DSWT Nursery stay for about three years. Once they are healthy and emotionally stabilized, they will be ready to make the journey to one of the DSWT’s three rehabilitation compounds elsewhere in Kenya. There they will be gradually introduced to a wild herd, returning each evening to a stockade where they can continue to receive care from their human “family.” This second phase of rehabilitation can take five to ten years, depending on how willing the wild herd is to accept the orphan into their group. To date, the DSWT has nurtured more than two hundred orphaned elephants, and has successfully reintegrated more than half of those into wild herds. Currently, the DSWT also cares for a twelve-year-old black rhinoceros, but he is not on public view. He will not be returned to the wild because he is blind.

The juvenile elephants were brought to the feeding area in three separate groups, youngest to oldest. The show was over at noon, when the third group was returned to its stockade. After a bathroom break, we left the national park and headed into the community of Karen on the west side of the city. This is an affluent suburb with several colleges and international schools, surrounded by large houses with well-kept gardens. We are told that Karen is home to the majority of Nairobi’s white residents; in addition, it is rumored to be the location for the temple that is to be built in Nairobi by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints within the next few years, although the temple’s exact site is yet to be announced.

Welcome to the Karen Blixen House

Our destination in this part of town was the Karen Blixen Museum, former home of the author of Out of Africa. Born Karen Dinesen in 1885 to a wealthy Danish family, she followed her adventurous fiancé (and half-cousin) Baron Bror von Blixen to Kenya, where their families had purchased land for a cattle ranch. Karen and Bror were married in Mombasa in 1914 and honeymooned on Crescent Island in Lake Naishava, which we saw yesterday.

The Blixens’ farmhouse, built in 1912, is now a museum

When the Blixens arrived at the family’s 4,000-acre property near Nairobi, the town was booming, having recently become the capital of the the British East African Protectorate as well as an exotic destination for European tourists. Local landowners convinced the Blixens that they should grow coffee, not cattle, and so their mutual uncle, Aage Westerholz, the primary investor, established the Karen Coffee Company. (The company was named not for Karen Blixen but for Westerholz’s daughter, who also was named Karen.)

A few coffee plants still grow on the Blixen estate

The coffee company struggled from its inception, first because the tensions of World War I caused labor and supply shortages, but mostly because the land itself was unsuitable for growing coffee, being at too high an elevation. (Our museum guide surmised that the Blixens had been intentionally misled by their local advisers, who didn’t want competition for their own cattle operations.) The Blixens’ marriage was even less successful than their business. Baron von Blixen was more interested in big-game hunting than farming and spent most of his time on expeditions away from home. Moreover, he was an unfaithful husband who–in the words of our guide–“gave his wife an unusual wedding present: syphilis.” In 1920, the Baron requested a divorce and left. Karen, who had been running the farm during his frequent absences anyway, took over official management in 1921 and did her best to keep the coffee company afloat.

Egyptian starcluster in the garden

Meanwhile, Karen had met and fallen in love with another big-game hunter, a dashing Englishman named Denys Finch Hatton. After the Baron’s departure, Finch Hatton moved into the Blixen home–although, he, too, was often away on safari. When he was killed in a plane crash in 1931, Karen was devastated. So, too, was the Karen Coffee Company, having suffered from drought and worldwide economic depression in addition to the altitude problem and general mismanagement. Karen gave up the farm and moved back to Denmark later that year, never to return.

Lantana adds color to the garden

Karen had begun writing a book while in Kenya, but back in Denmark she began working on it more earnestly. Having developed greater facility in English among the British colonial community in Kenya, she decided to write in English because she thought a book in English would be easier to publish and more profitable than a book in Danish. Seven Gothic Tales was published in the United States in 1934 under the pseudonym Isak Dinesen, and sold well after it was picked up by the Book-of-the-Month Club. Dinesen’s next and best-known book, Out of Africa, was written and published in 1937, simultaneously in both English and Danish. The film version of Out of Africa (1985) starred Meryl Streep as Karen and Robert Redford as Denys. (We hope the British Airways film catalog includes it so we can watch it again on our way home tonight!) Another of Dinesen’s books, Babette’s Feast, also was made into an excellent movie, which won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1988. (It’s in Danish, and it’s one of our favorites.)

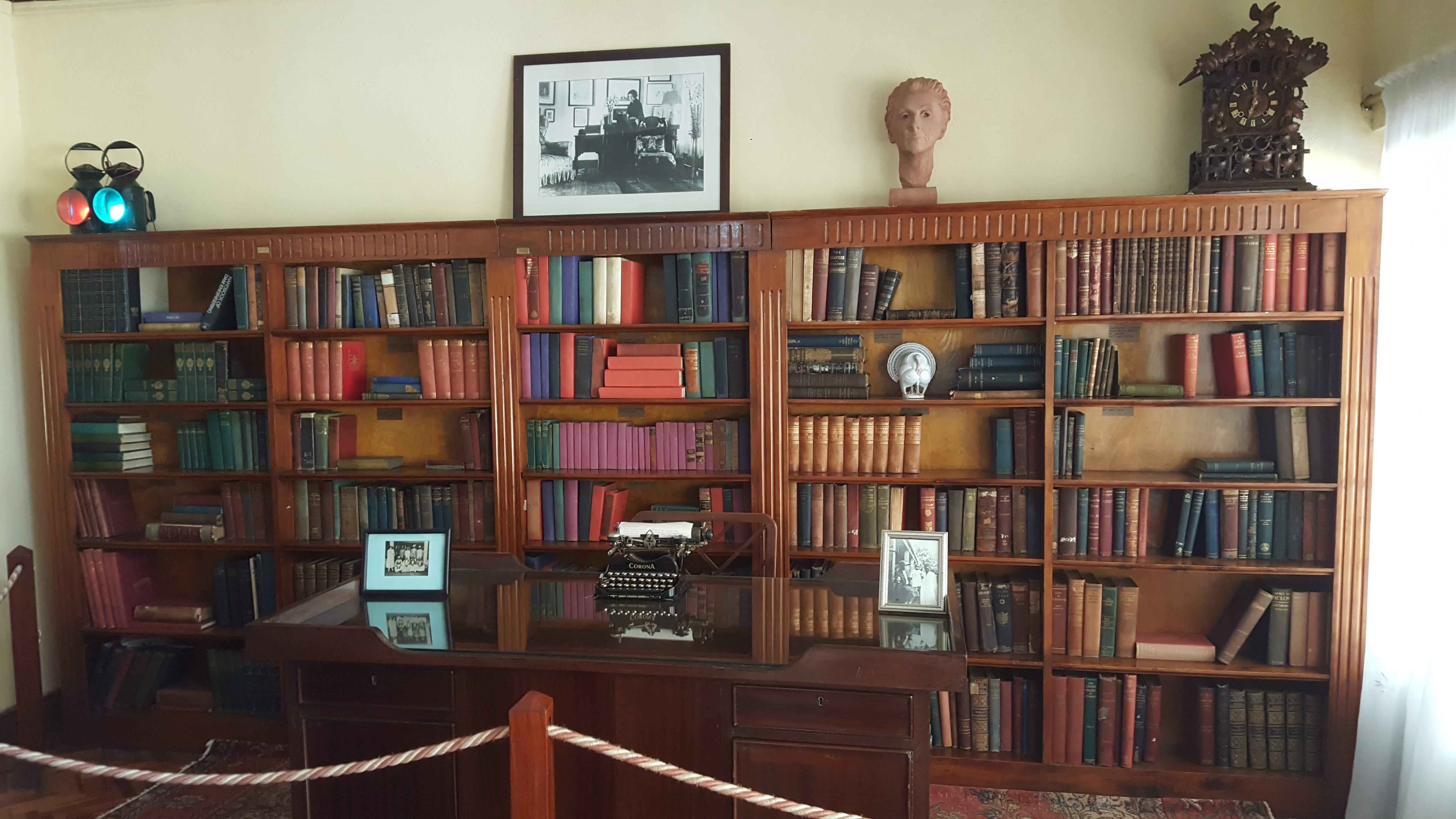

The living room and main entrance hall in Blixen’s farmhouse includes Karen’s desk and typewriter, as well as Denys Finch Hatton’s library

The leopard rug in the sitting area

The house was equipped with a telephone in the 1920s

The dining room, with the table as it was set for a 1928 visit from Edward, Prince of Wales. The portraits on the walls were painted by Karen Blixen and depict native members of her household staff: the boy at left became a judge; when the girl at the right married, she received a dowry of 250 goats

Jody examines a photo in Karen Blixen’s bedroom

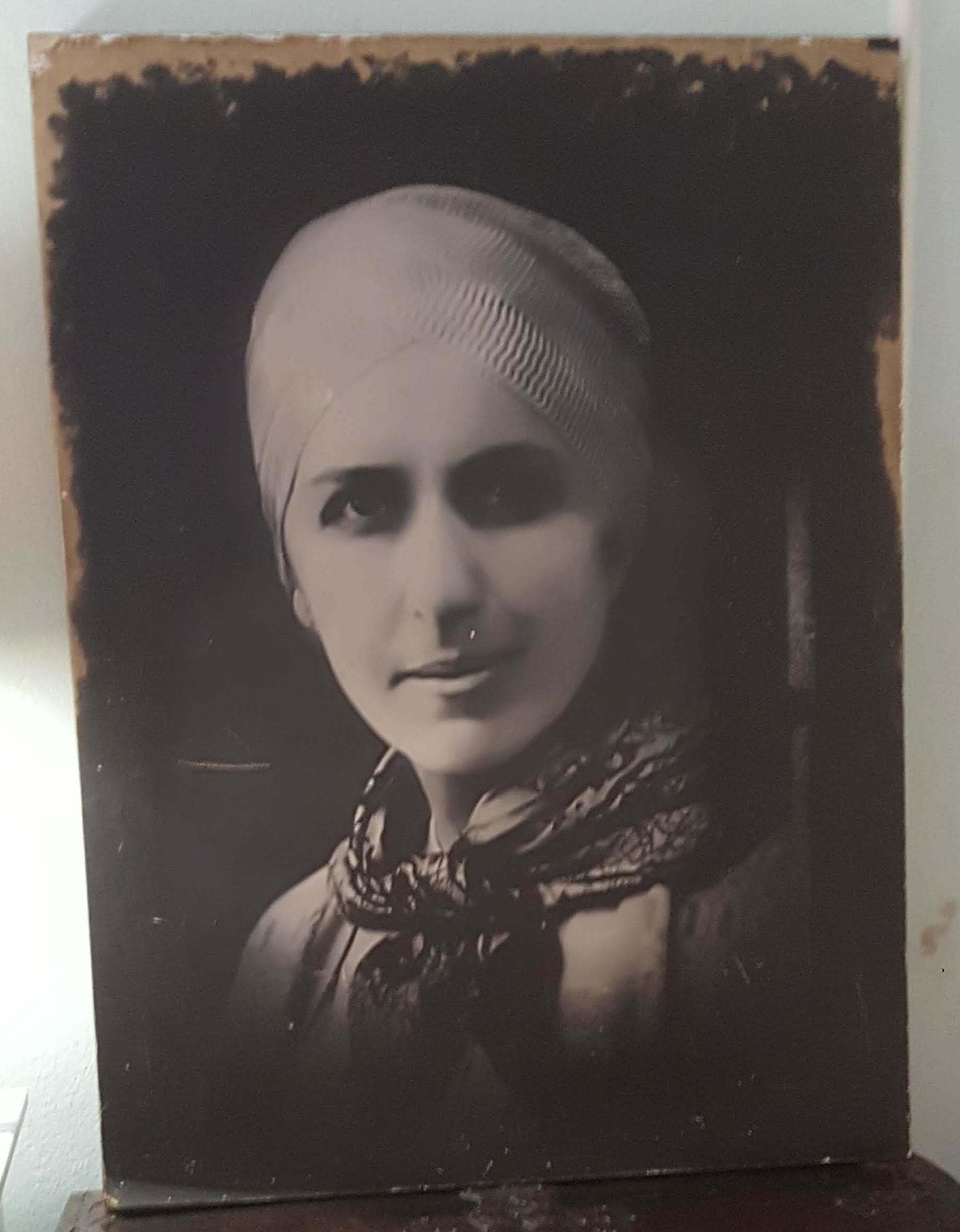

A photograph of Karen Blixen, who usually dressed like Somali women

Baron von Blixen’s bedroom, later used by Denys Finch Hatton. (We’re not sure which one shot the lion whose pelt is on the floor)

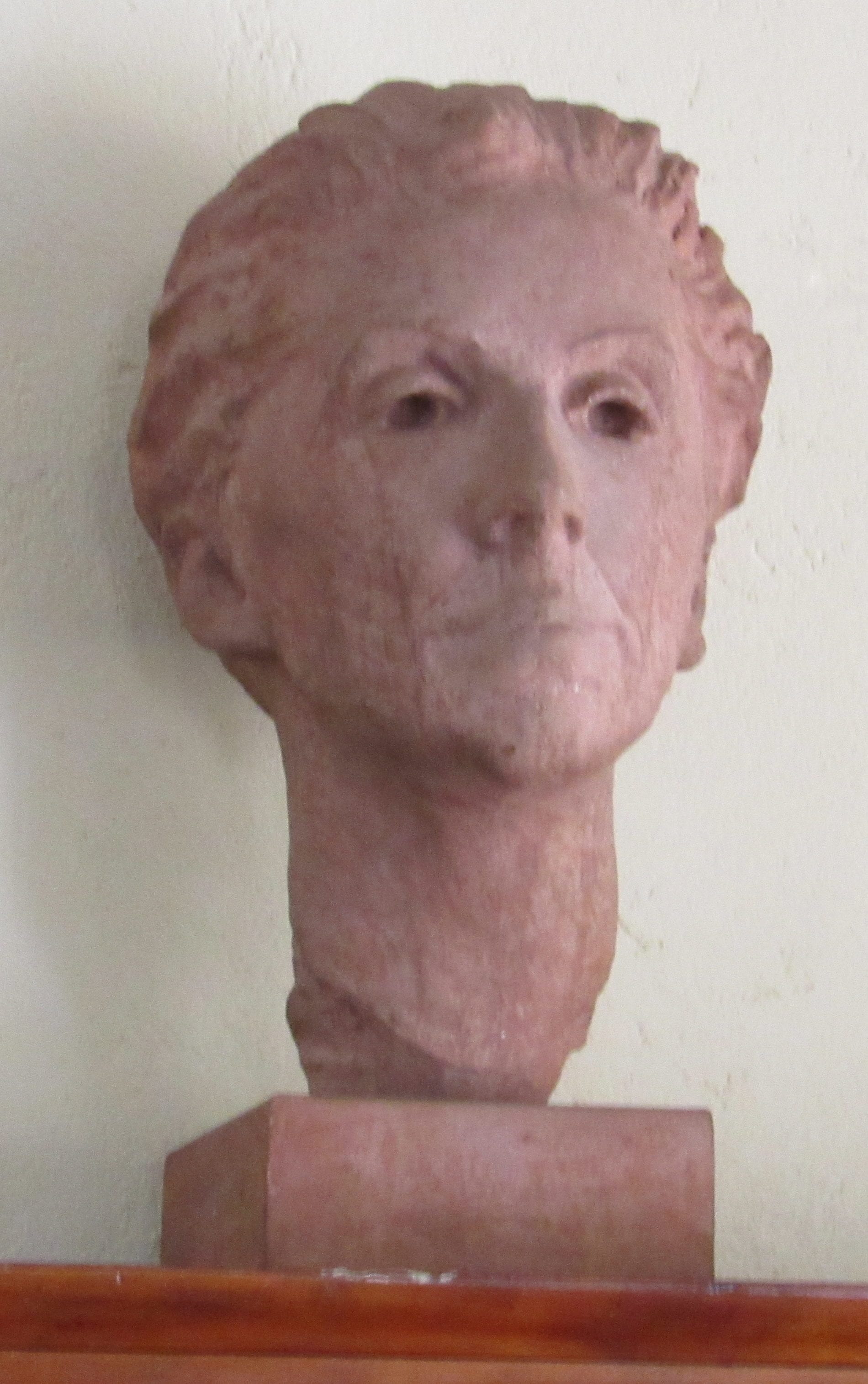

Bust of Karen Blixen

The bathroom–probably luxurious by 1920s standards

Crockery in the detached kitchen. (Note the wooden forms for drying socks)

A tabletop butter churn. Blixen trained a Kenyan cook to prepare European-style meals

The water filter used sand to remove impurities

A shady gallery at the back of the farmhouse

The hole in this old tree was made by a tree hyrax, a nocturnal mammal that is about the size of a small rabbit. According to an expert quoted in Wikipedia, “the male has a distinctive territorial call that starts with a series of loud measured cracking sounds, sometimes compared to ‘a huge gate with rusted hinges being forced open’. This is then followed by a series of ‘unearthly screams’, ending in a descending series of expiring shrieks.” Unfortunately, we did not get to hear this undoubtedly memorable call

Vintage farm equipment used on the Blixens’ property during the 1920s

When Karen Blixen left Africa, the estate was sold to a developer who divided it into 20-acre lots. He explained that the resulting community would be called “Karen” in honor of Blixen, not the Karen Coffee Company. The parcel that included the farmhouse went through several owners before being purchased by the Danish government, who presented it to the Kenyan government in 1964 as an independence gift. The estate was used as a college of nutrition until 1985, when the producers of Out of Africa requested access for filming; the house was then turned over to the National Museums of Kenya and restored as a historic site. Many of the original furnishings, which Blixen had given away or sold to friends in Nairobi, were returned, so the house now looks much as it did during the 1920s. Of course, the acreage once occupied by the failed coffee plantation is now occupied by schools, businesses, and multi-million-dollar homes in the prosperous suburb of Karen.

A local artist at work outside the museum

This plea was posted in the women’s restroom. We were curious to know exactly what is considered “the right way”

Our next stop was the Galleria Shopping Mall, where we were turned loose for about 45 minutes to look around and find something to eat. Most of our group took advantage of the Pizza Hut just outside the mall, while another handful went to KFC. Nancy and Michael again had planned ahead and stashed some yogurt, bread, and cucumbers from the breakfast buffet into their packs. That satisfied Nancy, but Michael succumbed to the temptation of Planet Yogurt and bought a cup of the frozen kind, feeling somewhat justified in his choice of passion fruit, mango, and papaya because it fulfilled his nutritional need for fruit.

Except for stores for a few local chains, the Galleria Shopping Mall just west of Nairobi National Park is not much different from a suburban shopping mall anywhere else in the world

This car wash and garage is located across the street from the Galleria Mall

As we ate, Jim Gee captivated our attention with a story about what had happened on a previous visit to the Samburu village within the past year. When the members of his Discovery XA tour divided to go inside individual homes, the host-guide for one group explained that because the village desperately needed money for the local school, each visitor was being asked to give another donation on top of the $20 each had already paid to tour the village. Being affluent, generous Americans, the visitors forked over another hundred dollars or so, which the host then pocketed. Even though this extra payment had been unexpected, those affected didn’t think much of it until they learned later that no one else in their group had been asked to give more money. When Jim heard what had happened, he was surprised and dismayed.

Jim shares a story about the Samburu

“That should not have happened,” he said. “That sounds like extortion, and I doubt that the chief would have condoned it. That village depends on maintaining good relations with tour groups, and if the word gets out that their people are demanding extra money from tourists, they’re going to lose business.”

At his next opportunity, Jim confronted the Samburu chief about the incident. As Jim had expected, the chief had known nothing about it and was gravely concerned that one of his tribesmen would commit such an outrage. He vowed that the offender would be brought to justice. Unfortunately, Jim was unable to help him identify the guilty party, because none of the visitors who had given the extra money could name or point out the man who had asked for it; the need to do so had not arisen until well after the Discovery XA group had left the village.

Shortly thereafter, the chief called a meeting of the tribal council and asked Jim to attend; Edwin went with him. All the village elders were present around the ceremonial fire, including each man who had participated in hosting the tour group on the day in question. At the council, the chief asked Jim to testify about what had occurred, and then demanded that the offender come forward and confess. No one did. The chief made the same demand a second and then a third time, and still no one came forward. So he pronounced a curse on the guilty man. He then asked all the assembled elders–including the unconfessed perpetrator–to stand up and chant the curse together to seal it. This was done in the Samburu language, so neither Jim nor Edwin understood exactly what was being said, but Jim told us that it obviously was deadly serious and admitted that both he and Edwin were somewhat spooked by the whole thing.

Here’s the kicker: That night, a 9-year-old girl from the village who had not been sick or injured and had no previous health issues unexpectedly died. The girl’s father, stricken by grief and shame, admitted that he had been the culprit in the extortion incident, and acknowledged that the curse had done its work. Despite his confession and the fact that he already had been severely punished for his misdeed, the man and his family were cast out of the village and banished from the tribe. No one knows where they went or what has become of them since. Jim says he feels terrible to have been involved in such a harsh outcome for someone who took a relatively small sum from people who really didn’t mind giving it, but he recognizes the need to respect tribal laws and customs and allow the Samburu to deal with offenders in their own way. Jim rejects the idea that the girl died as a direct result of a Samburu curse, calling it an unfortunate coincidence–but that’s a difficult argument to make with native Kenyans.

No doubt Jim could have enthralled us with more stories about his experiences in Africa (not to mention his other travels around the world), but it was time to move on. After everyone finished his or her lunch and had a chance to explore the mall, we got back in the Land Cruisers and headed toward the Giraffe Centre in Langata, only a couple of miles away. The sanctuary was founded in 1979 by a Kenyan of British descent and his American-born wife, who wanted to save the endangered Rothschild’s giraffe subspecies. Rescuing two young giraffes from land in western Kenya that was about to be developed, they began what has turned out to be a successful breeding program. Most Rothschild’s giraffes still extant live in zoos or sanctuaries such as this one. The few left in the wild can be found only in pockets within Kenya and Uganda, but since 1979, over three hundred Rothschild’s giraffes from the Giraffe Centre’s breeding program have been released into Kenya’s vast national parks, where they are subject only to natural predation.

No doubt Jim could have enthralled us with more stories about his experiences in Africa (not to mention his other travels around the world), but it was time to move on. After everyone finished his or her lunch and had a chance to explore the mall, we got back in the Land Cruisers and headed toward the Giraffe Centre in Langata, only a couple of miles away. The sanctuary was founded in 1979 by a Kenyan of British descent and his American-born wife, who wanted to save the endangered Rothschild’s giraffe subspecies. Rescuing two young giraffes from land in western Kenya that was about to be developed, they began what has turned out to be a successful breeding program. Most Rothschild’s giraffes still extant live in zoos or sanctuaries such as this one. The few left in the wild can be found only in pockets within Kenya and Uganda, but since 1979, over three hundred Rothschild’s giraffes from the Giraffe Centre’s breeding program have been released into Kenya’s vast national parks, where they are subject only to natural predation.

The markings of Rothschild’s giraffes are only slightly different from those of Maasai giraffes. Rothschild’s can be distinguished by the absence of coloring on their lower legs, which makes them look like they are wearing cream-colored socks

In 1983, the Africa Fund for Endangered Wildlife opened the Giraffe Centre’s education facility at the 60-acre preserve, where school children and other visitors can learn about giraffes and wildlife conservation efforts. The education building includes an outdoor gallery where visitors can feed the giraffes–the Centre’s most popular feature. It was kind of startling to realize how big these creatures actually are as they approached and eagerly ate right out of our hands. Vicky was the only one of our group brave enough–or maybe foolish enough– to try what some other visitors were doing: placing a pellet between her own lips to entice a giraffe to “kiss” her. (Nancy declined the opportunity, explaining: “I kissed the Blarney Stone, but I have no interest in kissing a giraffe.”)

Jody feeds a giraffe some pellets, which are made of compressed corn, wheat, grass, and molasses

Inside the education building, we learned that giraffes have special valves in their circulatory system to help control the flow of blood all the way up the neck to the head. Giraffes also depend on suspensory ligaments in their legs to take some of the burden of supporting their weight–which can exceed 2,000 pounds–off their muscles and bones. We had a chance to heft a leg bone, which was as heavy and dense as an oak beam. Such strong bones not only support weight, but also allow giraffes to defend themselves with a deadly kick.

The Giraffe Centre is also home to some warthogs and more than 150 bird species

Eric, Pam, Barry (mostly hidden behind Vicky), Eva, and Jim outside the Giraffe Centre’s gift shop

Abandoned construction sites abound in Kenya, both in and beyond Nairobi. This concrete skeleton provides an incongruous backdrop for the sharply dressed pedestrian at the right

Both rush hour and rain had begun by the time we left the Giraffe Centre, so we spent nearly an hour snarled in traffic even though the restaurant we were headed for was only a few miles away. While we were on the road, Amos pointed out Kibera, the largest slum not only in Nairobi but in all of Africa. Population estimates vary because it’s hard to get an accurate count of people who live in unauthorized housing, but the number of Kibera residents is thought to be at least 250,000. Nairobi’s 2.5 million slum dwellers account for 60 percent of its total population, living on only 6 percent of its land. Most earn less than $1 per day–if they are employed at all. Few have access to basic services like clean water, sanitation facilities, and electricity, let alone safety services, medical care, and regulated schools. From the highway, all we could see of Kibera was a tightly-packed mass of corrugated metal roofs, but we could imagine its miseries.

Kibera occupies the lowland between some nice hilltop townhomes and the high-rise office buildings downtown. Last month, a portion of the slum was razed to make way for a new highway, displacing an estimated 30,000 residents

Our view of Kibera had been distant and brief, but the picture pricked our consciences yet again as we walked into Carnivore, one of Nairobi’s best-known restaurants, and proceeded to consume more food than any of us really needed.

The restaurant describes its menu as “A Beast of a Feast”

Carnivore

Tonight’s banquet was the final event of our tour, so we tried to focus on celebrating the wonderful time we’ve had together during the past ten days rather than speculating on how many impoverished families could have been fed had we donated the extravagant meal to a local aid organization and dined instead on yogurt, cucumbers, and a hunk of bread.

Our banquet area in the lanai. A couple of vervet monkeys scampered through the foliage on the roof while we ate

Mark, Lynn, Dyrk, Jody, Jan, Steve, Jim, Roger, Nicki, Norene, Kara, Amos, Nancy

Edwin, Geoffrey, Mike, Vicky, Paul, Jen, Eric, Pam, Eva, and Barry. Margy and Bryce are at the table behind

The host led us through the restaurant to a lanai at the rear where a long banquet table had been set for our group. It was still raining lightly and a little chilly, but a couple of charcoal heaters near our table had been lit to keep us warm. The waiters took our drink orders and then brought passion fruit juice for us to sip while they described how the rest of the meal would unfold.

As its name implies, this restaurant is all about meat; everything else we were served seemed a bit perfunctory. The first plate contained an unembellished cobette of starchy maize.

Maize cobette

Lentil soup

The corn appetizer was followed by an undistinguished lentil soup, accompanied by a light-textured wheat bread that was pretty good. Next came a tiered serving tray that held enough lightly dressed lettuce leaves, sliced cucumbers, tomatoes, and avocados to constitute a salad for one person, but apparently the management thought it would be enough to satisfy the six people at our table. (The management was not wrong, because Nancy ended up eating most of it herself.)

At that point, the waiters began bringing out a panoply of meats: pork spare ribs, beef sausage, grilled chicken, roast turkey, roast beef, roast pork, roast lamb, roast crocodile, and ostrich meatballs. Most of these choices were presented on spits, from which the waiters would carve slices for us to sample. A lazy susan in the middle of each table offered a variety of accompaniments: fruit salsa to go with the pork, wildberry sauce for the poultry, tomato relish for the beef, mint sauce for the lamb, and garlic sauce for the crocodile. Somewhere amid the meat service we each got a small potato, but otherwise the parade of sizzling fat and protein continued unbroken for more than an hour.

Turkey

Chicken

Beef

Pork

Lamp

Ostrich meatball and crocodile

Some Carnivore diners may be disappointed to learn that the menu does not include more exotic game meats (lion, hippo, or cape buffalo, say). This is a result of Kenya’s commitment to preserving rather than exploiting its wildlife. Only meat which has been obtained from sustainable sources–such as ostrich and crocodile farms–may be sold Kenya’s grocery stores or served in restaurants.

When we all had had enough–or more than enough–we “surrendered” by turning down the flag in the middle of the lazy susan as a signal to the waiters that it was time to stop proffering meat and take our dessert orders.

Michael’s “vegetarian” option with tilapia

Michael “surrendered” before he even began. Because he started having some twinges of intestinal distress this afternoon, he asked the waiter to bring him the “vegetarian” plate instead of the regular Carnivore fare–but even this included a tilapia fillet along with steamed vegetables and rice. He took small bites of several of the meats on Nancy’s plate (how could he pass up the opportunity to try crocodile or ostrich?), but his stomach was glad that he had not overindulged his carnal appetite.

Michael chose crème brulée for dessert

Nancy’s pineapple “pie” à la mode was more like a cake

As we waited for dessert to be served, fireworks suddenly erupted. At first we thought the sparkles in the sky were just part of the evening’s festivities, but then we realized that they were spewing from a light fixture on the roof of the lanai just above our table. For a few moments we were afraid that the thatch would catch fire, but the sparks soon sputtered out, leaving only darkness and the odor of singed electrical wiring.

We were not the only ones to appreciate the charcoal heaters behind our tables

More than the food , what we enjoyed most about this evening is that our Kenyan driver-guides had been invited to dine along with us. Nancy had the privilege of sitting next to Amos, who shares her love of avocados. He also confided that although he liked the meat, he would rather be eating ugali (the African version of grits or polenta) and his wife’s vegetable curry.

At the end of the evening, Jim gave a heartfelt tribute to our drivers, each of whom also took a few minutes to share their feelings about our week together. Edwin included an announcement that after two years with Discovery XA, Amos had finally earned an appropriate nickname: henceforth, he would be known on the CB network as “Mongoose.” (Everyone heartily approved.) We were sorry that Steven and Anthony were missing tonight, and asked Jim and the others to extend our appreciation to them. It is obvious that Jim and his team have established a real brotherhood and sincerely care for one another, and we are grateful that we could entrust ourselves to such a fine group of guides. They are really the ones responsible for the great success of our unforgettable Kenyan adventure.

Leave A Comment