This morning we could get up at our leisure. While we showered, dressed, and googled “Schumann Scenes from Goethe’s Faust synopsis,” Marty went out to the bakery and came back with some croissants and a Schokoladengebäck (chocolate pastry) for Michael, who favors that sort of thing. Marty also scrambled some eggs and whipped up a banana-pineapple-chia smoothie; he’s been feeding us well. The Google search yielded links to a few reviews of recordings and past performances, but no actual synopsis–which served to confirm our suspicion that even the experts can’t explain what the heck is going on in that opera.

Images of the Brandenburg Gate decorate glass walls at a U-Bahn station

Needing to do some paperwork and listen to at least a dozen of the two-hundred-plus audition recordings he’s received for the four soprano slots currently open in the Staatsoperchor, Marty sent us off on our own again today. Rather than take the bus or the U-Bahn, we decided to try the S-Bahn. The latter is a rapid-transit commuter train that has fewer stops and allows more city views than the mostly underground U-Bahn.

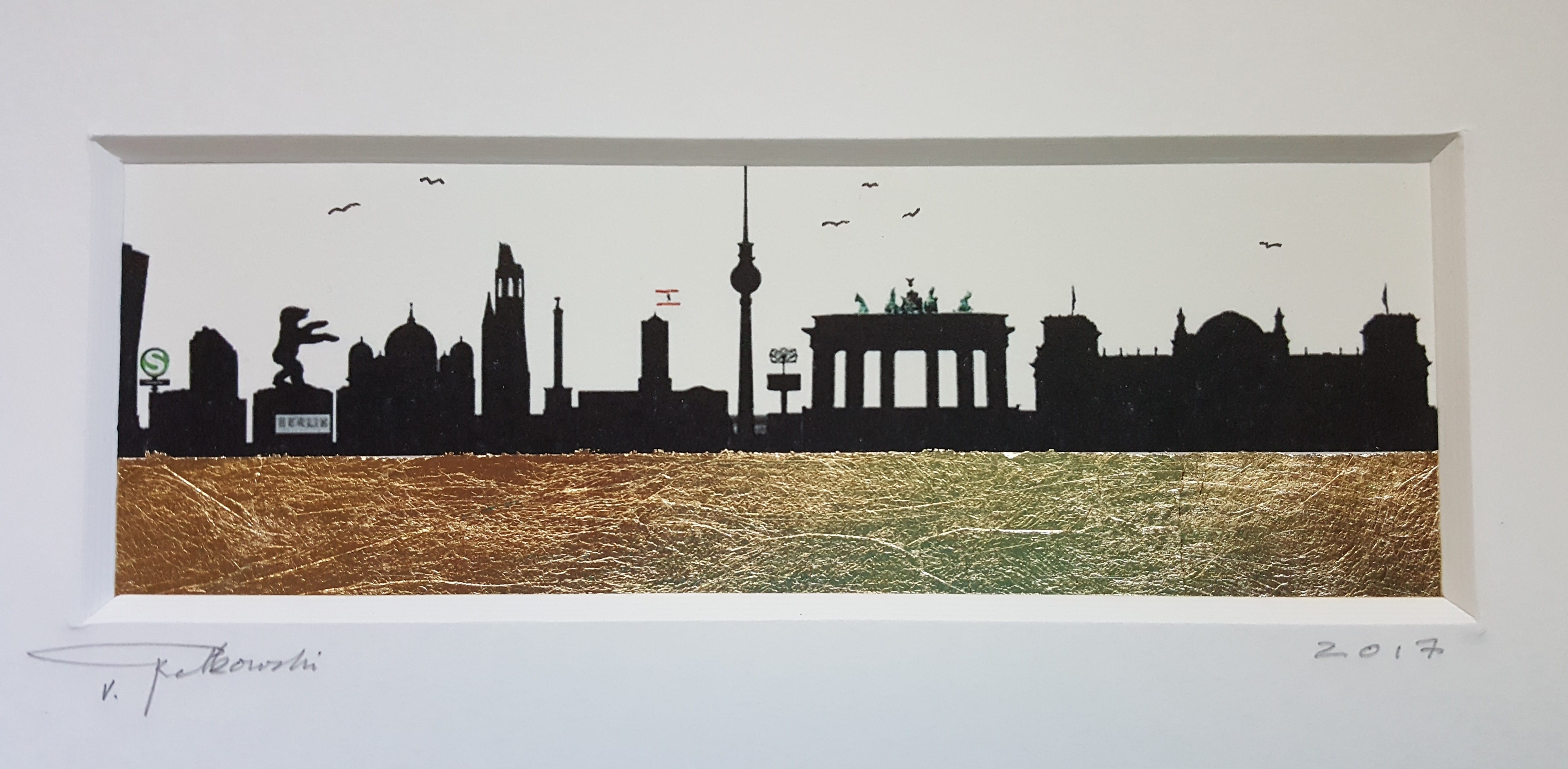

Checking a map, we figured out that the Hackescher Markt S-Bahn station not only was close to the first of our destinations for the day, but had the added attraction of its eponymous open-air market. Thus we spent a bit of this beautiful, windy Saturday morning strolling among the stalls, surreptitiously eyeing the other customers as well as the goods. In addition to food and flowers, vendors offered a variety of artisanal wares. We have established a tradition of buying a small painting or print to represent each major trip we have taken during the past few years, so we paid particular attention to displays of two-dimensional art and purchased a striking black-and-white print featuring the façades of Berlin’s most iconic buildings.

Hackescher Markt and the S-Bahn station

Berlin landmarks, print by V. Pelkowski

Berlin tram

The DDR Museum is only two blocks from the Hackescher Markt so we really didn’t need to ride the electric tram to get there, but when the bright yellow car stopped right in front of us, we decided that we might as well hop on. Now we can say that we have taken every form of public transportation that Berlin has to offer.

The mission of the DDR Museum is to document and describe life in the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (a.k.a. East Germany) from its founding in 1949 until its dissolution in 1990. Because East and West Germany were separate countries when we were born, all through our school years, and well into our children’s school years, it was a little startling for us to realize that by now, that fifty-year period of Germany’s separation has been over for more than a quarter century. A whole generation has reached adulthood since reunification, so the DDR Museum exists to preserve the collective memories of those who lived through it, and thereby educate those who didn’t.

The mission of the DDR Museum is to document and describe life in the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (a.k.a. East Germany) from its founding in 1949 until its dissolution in 1990. Because East and West Germany were separate countries when we were born, all through our school years, and well into our children’s school years, it was a little startling for us to realize that by now, that fifty-year period of Germany’s separation has been over for more than a quarter century. A whole generation has reached adulthood since reunification, so the DDR Museum exists to preserve the collective memories of those who lived through it, and thereby educate those who didn’t.

The place is a lot more fun than one would expect, probably because it is privately owned and thus free of the stultifying effects of official state sponsorship. The museum doesn’t take itself too seriously, despite the fact that the information it conveys can be deeply sobering. Surprisingly transparent and sometimes even graphic in its descriptions, the museum allows the depravity of the DDR’s socialist government and the desperation of its citizens to speak for themselves, with no high-minded lecturing to drive the point home.

Today the museum was crowded with visitors. The primary display space comprises a series of randomly placed walls of varied heights, each about eight feet long and one foot thick. These modular walls not only function as mounting surfaces for photos and placards with explanatory text, but they also contain modestly “interactive” elements, inviting visitors to open drawers, lift flaps, and slide panels to reveal more artifacts and information about a historical event or some aspect of daily life in the DDR. Although the museum space is ostensibly divided into three “theme” areas (State & Ideology, Public Life, and Family Life) and each module focuses on one subject such as education, industry, or the military, there is no definite starting point, nor any defined path through the museum. Visitors thus encounter a plethora of information in no particular order, and it is up to them to synthesize and make sense of it all. Perhaps this is an intentional metaphor for life in the DDR: while East Germany’s Socialist government ostensibly provided cradle-to-grave direction and support for its citizens, it left a lot of gaps that people had to find ways of bridging on their own.

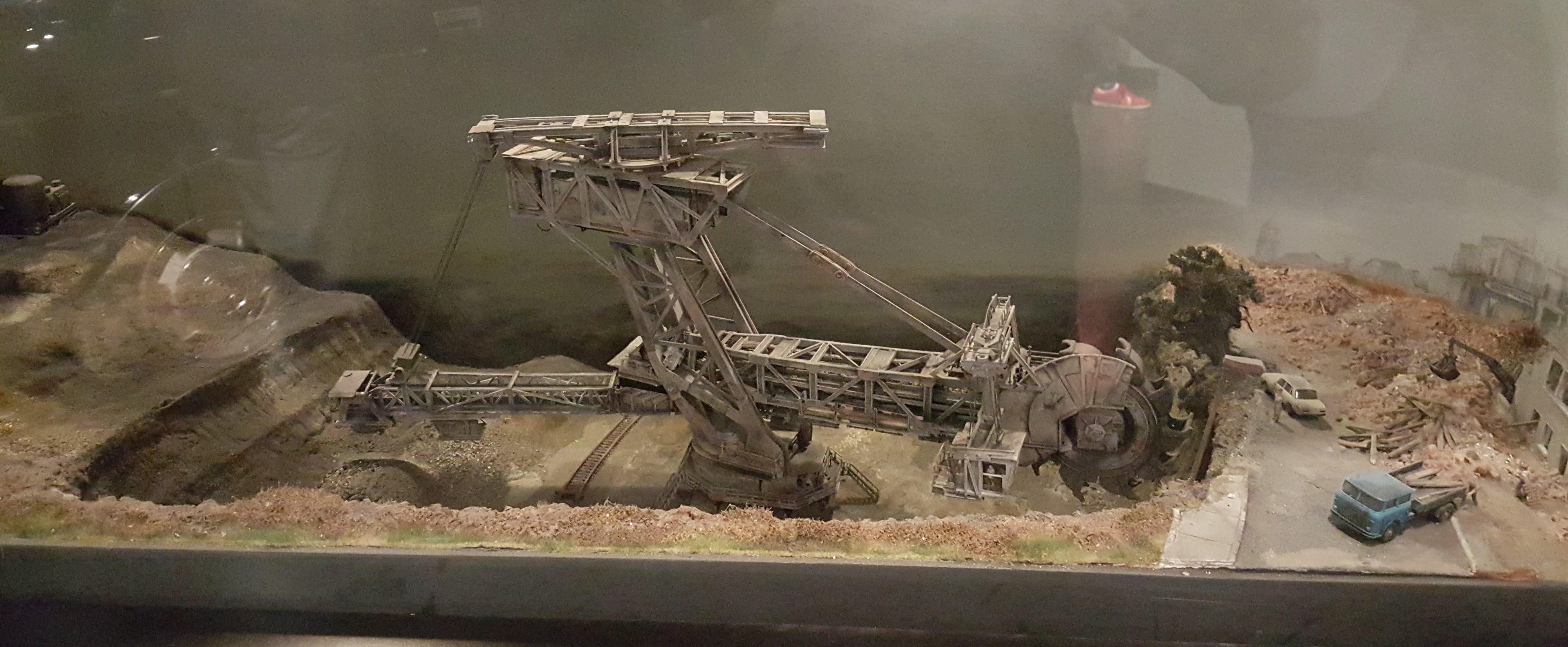

A model of an open-pit mine in the DDR Museum

One module that we found particularly interesting–and disturbing–focused on the devastating effects of poor management and official paranoia on the environment. Prior to 1970, the DDR had been a world leader in “green” practices, especially recycling–a necessity in a country with limited access to the vital raw materials of modern life. However, the country’s dependence on coal as almost its sole source of energy resulted in growing air pollution. Aging, outdated infrastructure in the DDR’s chemical industry contributed to water pollution and other environmental damage. The government was aware of the dangers but refused to confront them. In 1982, the Council of Ministers declared all official statistics on environmental issues “confidential,” forcing scientists and the media into silence–but the people whose health and well-being were suffering would not be muted. The Socialist state’s negative impact on the environment became one of the opposition movement’s major arguments.

A photo of Erich Mielke, head of the Stasi, keeps watch over a surveillance post

Peering into a prison cell

Surrounding the main display space of the museum are a number of smaller rooms, each also devoted to one topic under the broader themes of State & Ideology or Public Life. The first we entered was about the size of a broom closet, containing a desk with a bank of listening and recording devices. It replicates a surveillance post typical of those set up by the Stasi intelligence agency in residential neighborhoods and apartment blocks to monitor private conversations. Under the Socialist regime, not only did secret police spy on their compatriots, but ordinary citizens were encouraged to report any “deviant” and “unpatriotic” behavior to state officials, effectively destroying all sense of trust within communities. (If you’ve seen The Lives of Others, you’ve learned about the devastating effects of the Stasi’s surveillance system; if you haven’t seen that excellent film, we highly recommend it.) Another room at the perimeter represents the kind of prison cell where someone accused of criticizing a government official might have ended up.

We had been perusing the displays for nearly an hour before we noticed that other visitors were lining up to take an elevator just behind the entrance hall. Once we were ready to move on, we joined the line, too. The elevator itself is tiny–hence the long line. A few seconds after we got on and the door had creaked closed, the lights began to flicker and then went out. Nothing else happened for a few more seconds. Just when we had begun to wonder how long we were going to be stuck, the lights came back on and the elevator jerked to life. Our journey upward went through several more fits, starts, and blackouts, provoking nervous laughter among the passengers. Gradually it dawned on us that we were being treated to the kind of uncertainty and inconvenience that denizens of the DDR must have experienced every day. When the door opposite the one we had entered finally opened, we realized that we hadn’t gone anywhere at all; we simply gained access to another part of the museum–along with greater sympathy for people who are forced to endure even the smallest of hardships day after day.

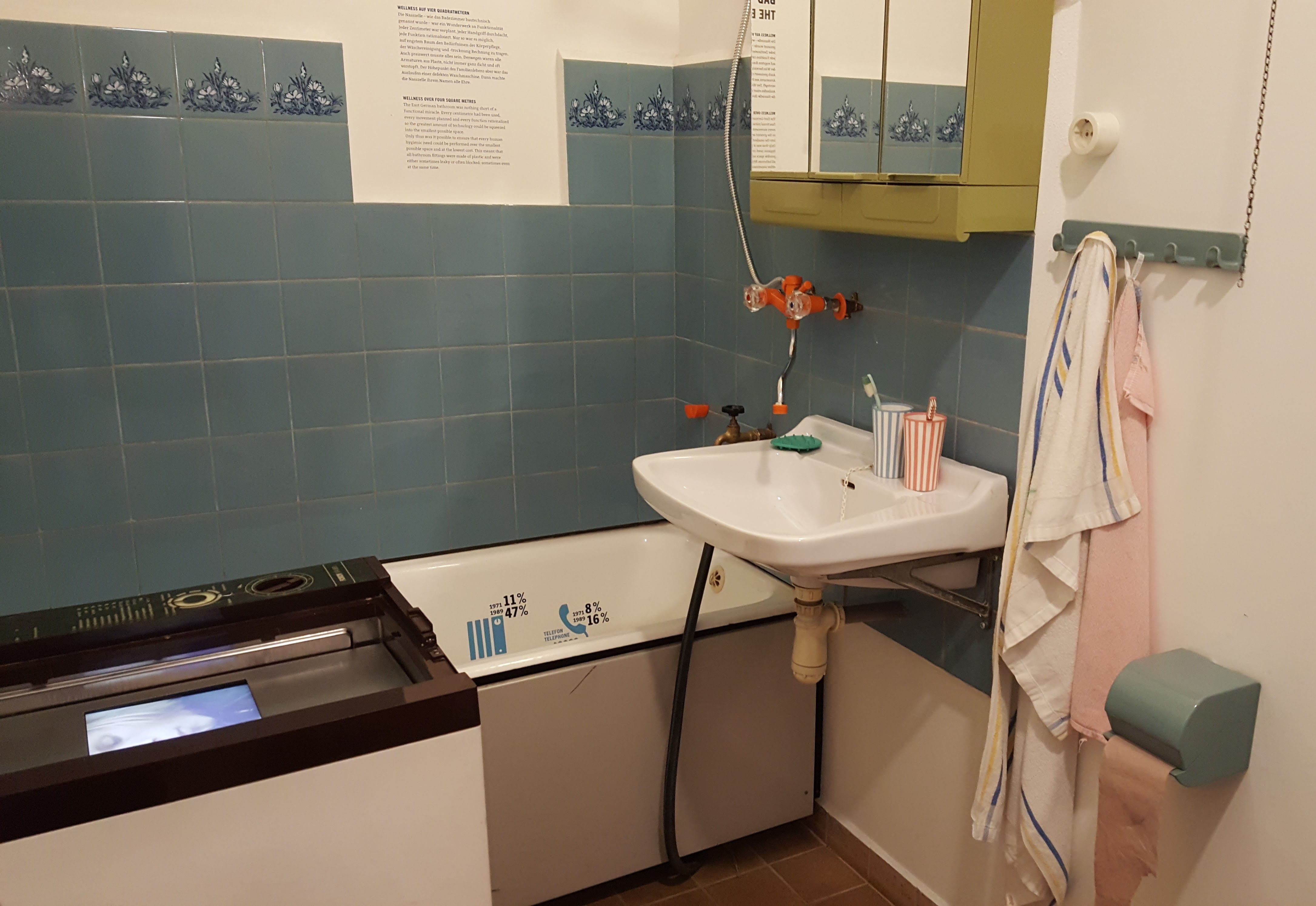

A bath and laundry room, set up for maximum efficiency

Canned goods produced in East Germany

The Family Life section of the museum replicates a hallway in a typical East German apartment block, circa 1975. Visitors may then enter a typical family residence, where the black-and-white television in a typical living room is tuned to a typical state-run broadcasting station. The adjacent, compact kitchen is outfitted with typical appliances, and the cupboards are stocked (but not filled) with typical East German canned goods–mostly cabbage, potatoes, and beets. Across the hall, the bathtub in the typically cramped combination bath and laundry room can hold a regulated amount of water (which, typically, may not be hot). Farther down the hall, we poked around typical bedrooms which, like the other rooms in the apartment, make efficient use of every scrap of space. Visitors may examine typical games and picture books in the children’s room, or even try on pieces of clothing from a typical teen’s wardrobe. In the parents’ bedroom, a wall placard invites visitors to speculate on the typical sex lives of couples with little time or money to spend on leisure activities outside their homes.

Although high-rise apartment blocks became a cliche of East German life, only one-third of the population actually lived in the type of flat on display in the DDR Museum. Other city-dwellers spent years in older, run-down housing, hoping their names would rise to the top of the waiting list to get into “full-comfort” flats like this one. However, many people preferred to stay in their dilapidated homes and familiar neighborhoods rather than move into featureless cinder-block towers. Hundreds of identical apartments in hundreds of identical buildings provoked East Germans to joke: “If you wake up and find that your wife has a new hairstyle and your toothpaste tastes different than it did yesterday, you probably went home to the wrong flat.”

We were amused to learn that the gardens of East German dachas often were decorated by the same type of plaster gnomes that populated Michael’s grandparents’ yard

Back in the State & Ideology area, we saw photos and read descriptions of the homes reserved for government officials, including the country dachas where they could escape the noise and grime of the city. But although the privileged class may have enjoyed somewhat roomier quarters than ordinary citizens and access to perks such as imported food, clothing, vehicles, and entertainment, their circumstances were far from luxurious. By the 1980s, conditions had deteriorated enough that even those in the highest echelons had to put up with air pollution, crumbling infrastructure, inferior consumer products, and chronic shortages of food and fuel.

A puppet theatre in the kindergarten

Jugend und Technik (Youth and Technology), a magazine published in the DDR, encouraged teenagers to dream big

In the Public Life area, we were intrigued by descriptions of how and what East German children were taught in school. A replica of a public preschool didn’t look unlike the kindergarten classrooms we attended ourselves, but it seems the curriculum was a bit different. Students were taught to respect authority and regard themselves as components in the great Socialist machine. Official restraints on the exercise of individual free will extended even to toilet training: toddlers in the DDR’s day care centers routinely were lined up on communal “potty-benches” and told to sit there until the last child had finished doing their duty. Older kids learned arithmetic by counting ranks of soldiers and tanks. In gym class, they practiced throwing dummy grenades. Officially, students were encouraged to value worker solidarity and–ostensibly–“world unity,” but because opportunities for them to confront the world outside East Germany were virtually nonexistent, most never learned how to deal with ethnic, racial, or religious diversity. Children were taught to assume that enemies were everywhere, so anyone who did not fit the mold was ostracized.

Michael takes a virtual drive through the streets of Berlin in a “Trabi”

One of our favorite exhibits in the DDR Museum was the full-size Trabant–East Germany’s attempt to produce its own version of the Volkswagen. Derided as “cardboard on wheels,” the notoriously unreliable automobile was ubiquitous within the DDR but rarely seen outside its borders because the car couldn’t meet other nations’ emission–or basic quality–standards. With no fuel gauge nor cooling system, let alone amenities like power steering or anti-lock brakes, the car described by its owners as “a spark plug with a roof” at least was easy to maintain because there were so few complex systems to break down.

Erich Honecker’s 1964 video projector, installed in the Cinema Hall of the State Council building–but rarely used

One thing that became clear to us as we read the explanations accompanying the museum’s displays is that prevailing attitudes during the Cold War differed considerably from prevailing attitudes during the DDR’s first years. It seems that in the early 1950s, East Germans had approached the rebuilding of their war-ravaged land with optimism and a desire to create an exemplary society based on Socialist principles. The problem was that they had few resources with which to build, and too much influence from the Soviets who eventually seized control. Although the Stasi had been organized in 1950, it did not become a serious organ of repression until the KGB essentially took over the German agency in the early 1960s–and it wasn’t only the proletariat who suffered. Even within the Politburo, competition and political intrigue made its private compound north of Berlin feel more like a prison than a retreat.

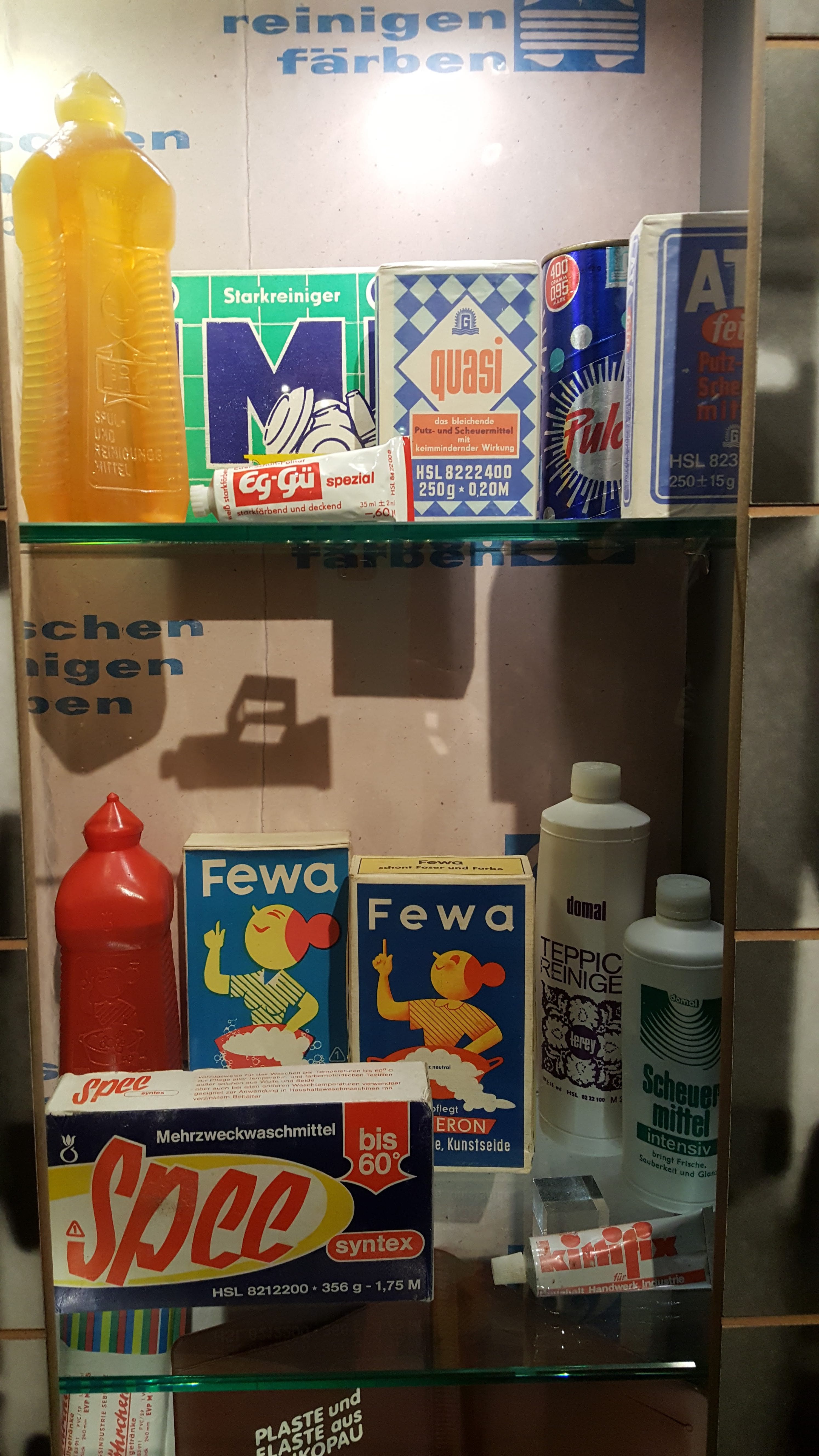

A cabinet of consumer goods produced in the DDR. The country’s supply chain could never keep up with demand

This pervasive atmosphere of mutual distrust contributed to the demise of the DDR, but the country’s true cause of death was economic collapse. Outmoded technologies and limited natural resources crippled every industry. Collectivization stripped farmers of responsibility for their own land and robbed factory workers of incentives to innovate. As a result, production and quality in both the agricultural and manufacturing sectors plummeted. Desperate for revenue, the DDR sent the best of its paltry output abroad, depriving its own citizens of decent consumer goods. Government ministers, paralyzed by fear for their own security, either ignored signs of economic and ecological disaster or pointed the finger elsewhere.

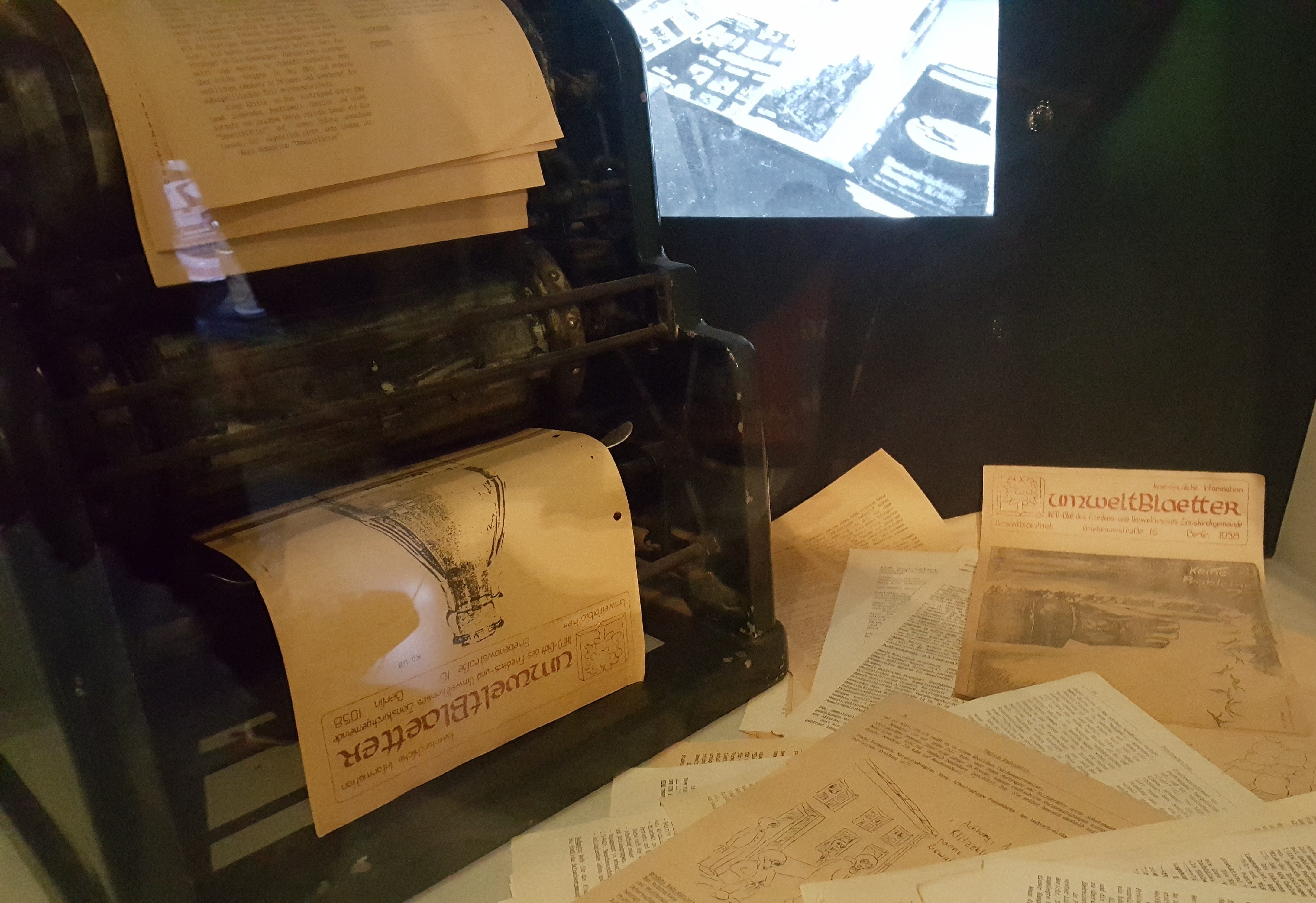

Umveltblaetter, an underground newspaper, was printed in a church basement

Disillusionment with the government’s refusal to confront environmental damage or even release relevant statistics eventually gave rise to a grassroots opposition movement. We think it’s significant that the opposition found safe haven in churches, where disaffected citizens could quietly gather to share information and commiserate. Churches also provided dissidents with means to produce and distribute pamphlets to raise awareness of environmental and human rights issues. However, the movement remained relatively passive until November 1987, when the Stasi raided the underground Umwelt-Bibliothek (Environmental Library) housed in the basement of a church in East Berlin. Two months later, protesters turned an annual Marxist memorial march in Berlin into a demonstration against repression. More protests followed. By the time municipal elections were held in May 1989, the resistance was better organized. Thousands went to the polls but defaced their ballots, indicating their refusal to continue rubber-stamping Socialist officials predetermined by the party. When winners were announced and it became clear that the election had been rigged as usual, thousands more joined the protesters. Emboldened by growing popular sympathy as well as by continuing support from the clergy, the resistance succeeded not only in standing up to the Socialist government, but eventually in knocking it down. By the end of 1989, the Berlin Wall had fallen, along with the repressive regime it represented.

A light fixture salvaged from the ill-fated Palace of the Republic, popularly derided as “Erich’s Lamp Shop” because hundreds of these illuminated the little-used building

Despite the DDR Museum’s frequent moments of comic relief, reviewing the country’s forty-year history had been an intense experience for us. We still had nearly two hours before we were supposed to meet Marty back at his apartment for dinner, but we didn’t have much mental and emotional energy left, so we just started walking. We crossed the Spree River by way of the Leibknecht Bridge and walked along Unter Den Linden, passing the Berliner Dom (cathedral), the Altes Museum (the “old” one where Greek and Roman antiquities are on display), and the Berliner Schloss (royal palace), which is currently under reconstruction.

The Berlin Palace, undergoing reconstruction

The original palace was damaged during World War II, but rather than repair such a monument to monarchy, the Socialist government decided to demolish it. In 1976, the Honecker administration erected the Palace of the Republic on the site. Besides being the seat of the East German parliament, the complex also included restaurants, an art gallery, a theatre, a bowling alley, and a 5,000-seat convention hall, but the public regarded it as an unnecessary extravagance and stayed away. Good thing. In 1990, the structure was revealed to be a public health hazard containing over 5,000 tons of asbestos and was permanently closed. Following German reunification, and after much heated debate about what to do with the site, the Bundestag finally tore down the “people’s palace” and decided to rebuild the Berliner Schloss as a museum and cultural forum. The exterior will replicate much of its imperial-era Baroque architecture, but the inside has been designed to serve more modern needs. However, some historic chambers will be reconstructed, and elements of archaeological interest will be preserved under glass floors so visitors can view them.

Berliner Dom

The Altes Museum

When we reached the Staatsoper–familiar territory–we decided to hop on a bus and go to the Kulturforum. This is a collection of buildings erected in West Berlin since the 1950s to house cultural institutions whose former homes had ended up on the wrong side of the Wall during the Cold War. We had been to the Kulturforum Thursday night for the Staatskapelle concert in the Philharmonie; now we headed back to spend an hour in the MusikInstrumenten-Museum.

The Kulturforum complex includes the Berliner Philharmonie

Musikinstrumenten-Museum Berlin

Founded in 1888 as part of the Royal Academy of Music, the Musical Instrument Museum now occupies a sharp-lined, modern facility with gleaming floors and lots of glass. We found a rack where we could hang up our dripping raincoats and then hurried to the display area, knowing that we had little time to examine the 3500 instruments in the collection.

Inside the Musical Instruments Museum

Single-stringed viols from the 18th century. Curiously, this type of instrument was called a “tromba marina” (marine trumpet) because the sound resembles that of a trumpet

1929 “Mighty Wurlitzer” theater organ, endowed with 1228 pipes, 175 stops, and 43 pistons. The museum offers regular recitals, but not during our visit, alas

Virginal, made in Augsburg c. 1600

Organ built in Bath, 1820

Clavichord, Dutch, c.1700

Cembalo, made in Antwerp, 1618

French horns evolved from hunting horns during the 18th and 19th centuries as more tubing and valves were added to extend the instrument’s range

An early pianoforte

Street organ

Benjamin Franklin’s glass harmonica

After years of using the Krummhorn solo voicing on the organ at church, Michael finally got to see some actual krummhorns, double-reed wind instruments that were popular during the Renaissance. These date from the mid-17th century

Dinner chez Mr. Wright

We could have stayed longer, but Marty was expecting us back at his apartment for an early dinner; the three of us had tickets for another 6:00 p.m. concert. Having skipped lunch, we were hungry, so the roasted eggplant with chickpeas and tomatoes Marty had prepared was especially satisfying. After dinner, we headed once again to the Staatsoper.

Chandelier in the Staatsoper salon

We were in for a treat. The Staatsoper had invited Zubin Mehta and the Vienna Philharmonic to participate in its grand reopening festivities this week. Part of the Staatsoper’s renovation involved expanding the stage area in front of the proscenium for orchestral concerts, so the strings and woodwinds now sit where they can be heard unfettered. Tonight’s concert proved that repositioning to be an acoustical triumph. The first half of the program included Brahms’ Tragic Overture, followed by Haydn’s Sinfonia Concertante. After intermission, the orchestra played one of our favorites, Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra. All of us had heard it performed and listened to recordings many times previously, but even Marty agreed that tonight’s performance was among the best of any performance of any piece we’ve ever experienced. For us, heaven will now have to include Zubin Mehta and the Vienna Philharmonic playing Bartok.

Zubin Mehta as we first encountered him

At age 81, Zubin Mehta has been around even longer than Daniel Barenboim, conducting major orchestras in major halls all over the world. In 1962, at age 26, he took over the Los Angeles Philharmonic and remained there until 1978, so Nancy had the opportunity to see him conduct a few times as she was growing up. Both of us had a particularly memorable chance to see him in December 1976, just before we got engaged. Michael had spent the week after Christmas in Southern California, ostensibly visiting his sister who lived in Riverside but actually using her house as a base from which to visit Nancy in Fullerton. Nancy’s parents were season subscribers to the LA Philharmonic, and had tickets to a New Year’s Eve performance that they couldn’t use because they had to chaperone a church youth dance that night, so they gave the tickets to us. Zubin Mehta was on the podium, his dark curls flying along with every flourish of his baton. We don’t remember what else was on the program but the last number was Ravel’s Bolero, which the orchestra played with smouldering intensity as it built toward the fiery climax. Just as the music reached that crucial key change a few measures from the end, a “Happy New Year!” banner suddenly unfurled at the back of the stage and confetti rained from the rafters. The moment was unforgettable.

(Michael’s less theatrical marriage proposal occurred two weeks later, during an after-dinner conversation with Nancy in his Provo apartment. The next morning, Marty was the first to be told of their engagement.)

Zubin Mehta at age 80 (photo credit: Steve J. Sherman)

We’ve changed a little in the forty-plus years since that New Year’s Eve in Los Angeles, and so has Zubin Mehta. His dark curls have grayed, and his conducting is not as energetic as it was in 1976–but it doesn’t need to be. He no longer has to demand that the orchestra follow him because he’s already won their trust and affection; you can see that in their faces. So now all he needs to do is invite them to come along–and they do. We were impressed that Mehta did the entire concert from memory, which means that his mind is probably in better shape than ours. Then he and the entire orchestra did the encore from memory, too: a Strauss waltz, played in perfect, joyful unison despite the little hesitations that breathe life into a strict 3/4 meter. The whole crowd seemed to float out of the concert hall tonight. We certainly did.

Trio of eternal friends

Back at Marty’s apartment, we ended the evening with more homemade “healthy” cookies and herbal tea, feeling so privileged to have had this priceless experience together as dear friends.

Leave A Comment