New Discoveries

In addition to returning to our favorite Paris sites, we decided to visit some places we had missed in the past, and seek out others that either had not existed until this century or were off the usual tourist track. Here is our list of new (or at least, new-to-us) discoveries. We’ll present them in alphabetical order, although we planned our visits geographically to make the most efficient use of our time, energy, and transit passes.

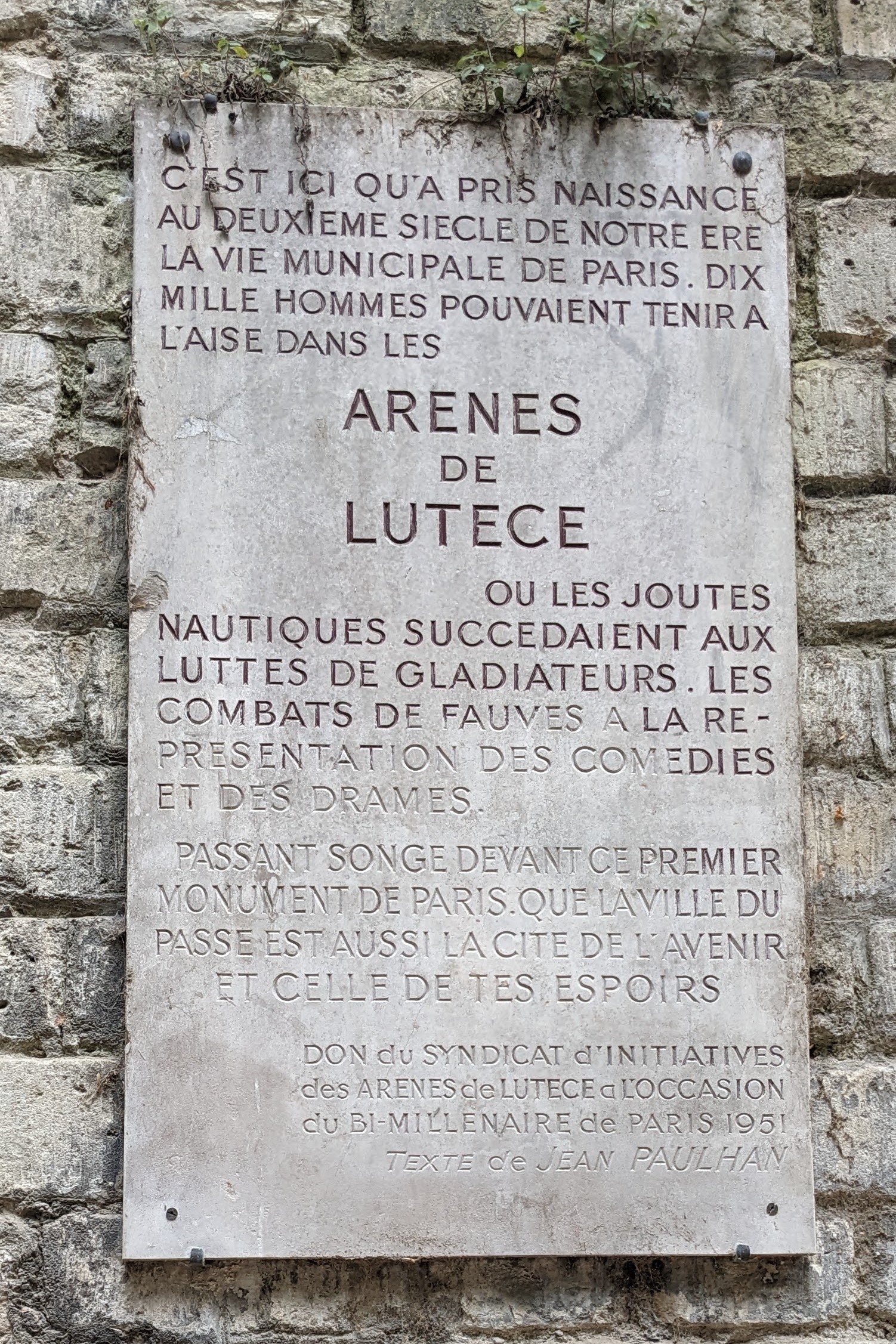

Arènes de Lutèce

Among the most important Roman ruins in Paris, this first-century amphitheater could hold 15,000 people for performances and other entertainment, including gladiatorial combats. Lutèce is the French form of Lutetia, the Latin name of the original settlement on the Seine that eventually became Paris. The name Paris was derived from Parisii, the name of a Celtic tribe that populated the area in the third century before Christ.

On the day we visited, the only entertainment provided in the arena was people-watching, and even that was scarce. No doubt kids use the space for soccer after school.

Arena |

Viewing stand |

Description |

Bateaux Mouches

In our younger, more arrogant days, we had deemed a Seine river cruise too kitschy to even consider—something only tourists would do. Maybe the advancing years have made us more humble (or maybe just more content to sit down and relax) because we had a great time cruising up and down the river for 90 minutes, seeing familiar monuments from new angles. We felt at one with all the people—Parisians and tourists alike—lining the banks of the Seine, basking in the warmth of a summer evening and watching the sun set behind the Eiffel Tower. C’est la vie—in the most positive sense of that phrase.

Bateaux Mouches dock |

Bateaux Parisian (a competitor of Bateaux Mouches) |

Pont Alexandre III from the boat |

Palais de la Cité and Conciergerie from the boat |

Louvre from the boat |

Musée d’Orsay |

Sunset over the Pont de la Concorde andGrand Palais |

Eiffel Tower |

Pont Marie |

Canal Saint-Martin

The Seine is not the only waterway in Paris. In 1802, Napoleon I ordered the construction of a canal in the northeastern part of the city to provide clean water to the growing populace. Ironically, funds to build it were raised by instituting a new tax on wine. The prefect of Paris recommended using the new conduit to connect the Seine with the Canal de l’Ourcq, part of an existing system of canals outside the city limits. In addition to a trench for the waterway, a series of locks needed to be built, so construction was not completed until 1825. Once it opened, the Canal Saint-Martin became an important means of transporting goods as well as fresh water through the city. A little less than 3 miles (4.8 km) long, the canal is still plied by barges carrying building supplies and such, but mostly it is used for pleasure boating. About half of the canal disappears from sight as it passes through a series of tunnels and under bridges built to accommodate more surface traffic, but along the stretches where it is open to view, Canal Saint-Martin encourages people to slow down and enjoy life at a calmer pace.

Canal Saint-Martin |

Canal Saint-Martin locks |

Alfred Sisley, Canal Saint-Martin, 1872 (painting in the Musée d’Orsay) |

Moulin Rouge

A cruise on the Bateaux Mouches might be considered kitschy, but there’s no question that the revue at the Moulin Rouge represents the height of lowbrow entertainment. The “Red Mill” also represents big business, with ticket costs that rival those of a good show in Las Vegas. At the Moulin Rouge, a couple of hundred dollars buys you one of ten uncomfortable chairs at a table designed to seat eight, wedged so tightly into a salon packed with other crowded tables that they’d probably have to use a crane to extract anyone who needed to use the toilet before the end of the show. We were advised to arrive early because seating is first-come, first-seated, although patrons who reserve an overpriced dinner ahead of time get escorted to tables closer to the stage. We’re not sure that would be an advantage, however, because proximity to the performers might mean that you could see exactly how much makeup was required to create the illusion of flawlessness in row after row of featureless chorus girls. We had already enjoyed an excellent dinner just up the street at Le Sanglier Bleu (see Three Days in Paris – Part 1) before joining the queue outside the Moulin Rouge, so when the doors opened we were directed to a table in the second tier of the grande salle. Although we were wearing some of our nicer traveling clothes, we were seriously underdressed; most other patrons were decked out in suits, ties, evening gowns, and glittery jewelry, mais tant pis (but too bad)—no one paid much attention to us anyway. Once the show began, all eyes were on the stage, where the performers managed to be both decked out in their glitziest and seriously underdressed.

Our observations: The Féerie (Fairy) revue featured a lot of bare-breasted women, but the effect was objectifying rather than sexualizing. All were white except one or two with light-brown skin, and all were uniform in size and shape: medium-tall, fashion-model thin, long-legged, and small-breasted. Their costumes were constructed with a minimum of fabric and a maximum of rhinestones, sequins, and feathers, and were accessorized by extravagant headdresses and sparkly stiletto heels. The men displayed slightly more racial diversity than the women and generally showed less skin, and while we would not describe them as “he-men,” their bodies might be defined as “ripped.” Michael noted that all were entirely free of body hair. Chorus lines of both sexes executed their can-cans and other routines with precision, but the dancing was not particularly inspired; we’ve seen more creative choreography in musical theatre productions at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music, and even at some local high school shows. We enjoyed watching the three talented women who headlined Féerie (whose names we never learned); all had strong voices and dance skills, and they worked especially well together, at one point donning dark wigs to imitate The Supremes.

But this brings up an aspect of Féerie that we found more offensive than the sterile sexual objectification: its unapologetic cultural appropriation and willingness to employ stereotypical tropes. One act, set in Indonesia in an undefined past era, featured a French corsair whose ship is welcomed into port by a phalanx of exotic Javanese dancers, and who must tame live tigers and pass through a pit filled with real, writhing pythons in order to assure a demure but gaudily dressed maiden of his undying love. The last act was ostensibly a tribute to “beautiful, liberated women” through the generations from 1789 to the present—although “the present” didn’t seem to extend into the twenty-first century; Gloria Gaynor’s 1978 anthem, “I Will Survive” (again, performed by white women in dark wigs) was about as far as they got. To bring the revue up to date and validate its salute to “liberated women,” they could at least throw in a Taylor Swift number. But Féerie has been playing at the Moulin Rouge since Swift was a preteen, and a lot more about the show would have to change to bring it into alignment with its socio-political pretensions. After seeing Swift and company in the film version of her 2023 Eras tour, Nancy couldn’t help but notice the contrasts between it and the Paris revue. Physically, Swift—another slim, small-breasted white woman—might have blended very easily into a Moulin Rouge chorus line, but her exceptional energy and charisma would have made her too much of a standout. And notably, the back-up performers sharing the stage with Swift were individuals of all shapes, sizes, colors, and genders; the only characteristics they seemed to have in common were abundant talent and an obvious love for what they were doing. The Eras entertainers exuded joy; the French performers came across as jaded.

But it wasn’t all bad. The Moulin Rouge show also included some amazing entr’acte spectacles. One was a strongman who could (among other things) stretch his entire body out horizontally while balancing on one hand; another could balance himself on a plank atop a rocking tower of balls and barrels. A female acrobat dressed only in a thong plunged into a transparent water tank and proceeded to cavort under the surface with some live eels, apparently never coming up for air during the whole five-minute act. A pair of roller skaters executed a series of spins, flips, and throws, all within the confines of a circular platform that couldn’t have been more than eight feet in diameter and was raised several feet off the floor. (That was our favorite.) In the final analysis, we decided that we were glad we had had the Moulin Rouge experience, but we don’t feel the need to ever go again.

Moulin Rouge exterior |

Queue to enter the grande salle |

La grande salle, packed to the gills |

Les danseuses. (Patrons are not allowed to take photos in the grand salle, so this came from the Moulin Rouge’s website) |

Better-dressed patrons eye more bling on sale in the obligatory gift shop |

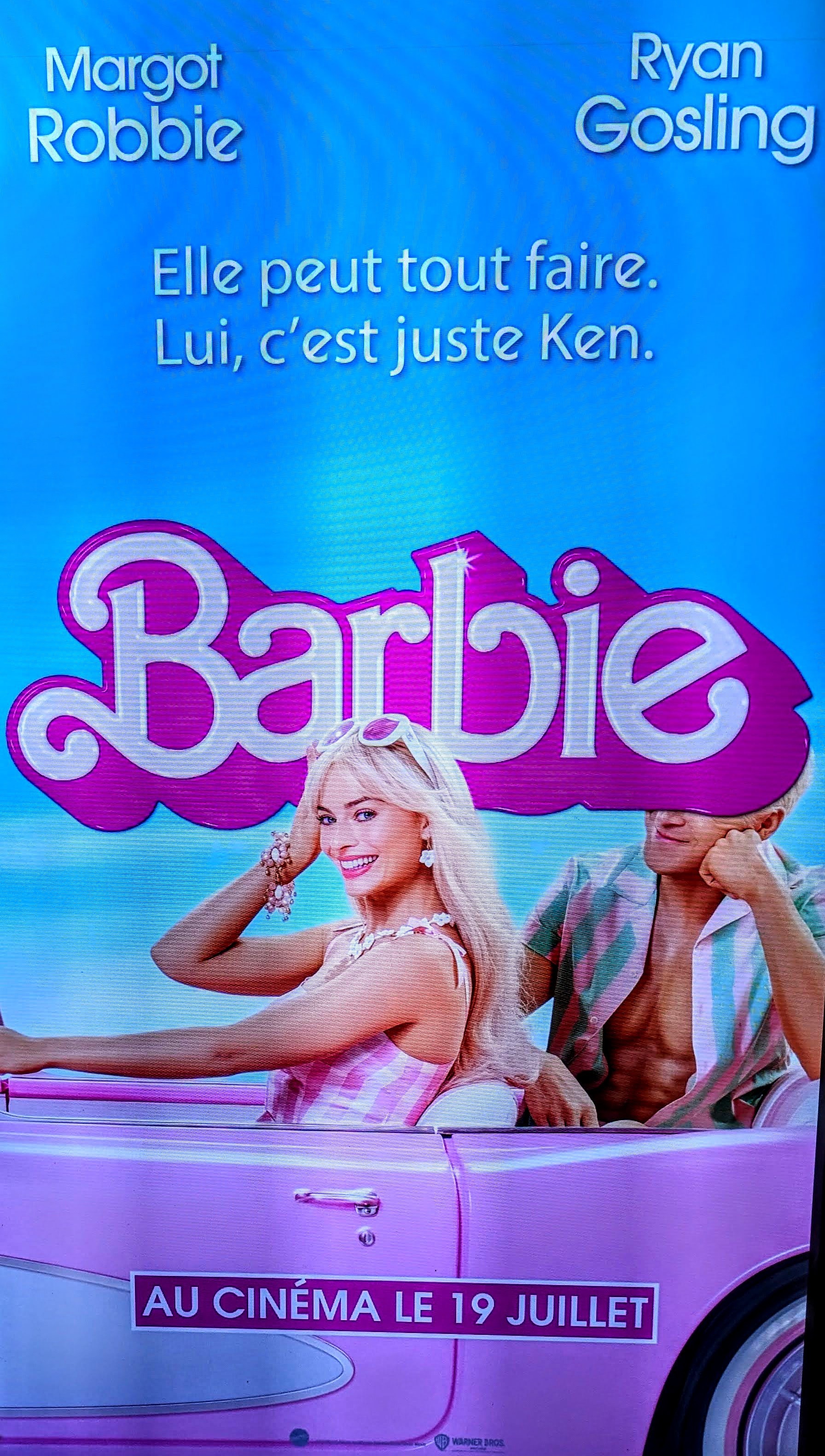

Parisians were anticipating the opening of the Barbie movie as much as Americans; Barbie herself could have fit right into the chorus line at the Moulin Rouge |

Musée des Arts Forains (Museum of Fairground Arts)

Back in the seventeenth century, the mayor of Bercy, a town on the Seine just outside Paris, convinced Louis XIV to grant the village an exemption from the import tariffs levied on merchants from towns farther from the capital because of Bercy’s proximity to the city’s southeastern gate. As a result, by the nineteenth century, Bercy had become a thriving port with the largest complex of wine warehouses in the world. Eventually, as the population of Paris grew and its geographic boundaries spread, the village of Bercy was incorporated into the city and the wine traders moved elsewhere. Some of the Pavillons de Bercy (warehouses) were torn down to make way for residential buildings; some were repurposed as other types of commercial spaces. One cluster of former wine warehouses got a completely new life in 1996, when an antique collector who specialized in classic carnival paraphernalia set up a museum in the Pavillons de Bercy to display his collection of “curiosities.” These include amusement park game booths, wooden mannequins, waxwork figures, merry-go-rounds, and more—all dating from 1850 to 1950.

Visiting the Musée des Arts Forains (Museum of Fairground Arts) was great fun, because we had the opportunity to not only look at examples of antique carnival games and rides, but to actually use some of them. We rode on a few different carousels, the most unusual of which put riders on bicycles instead of wooden animals and utilized pedaling power to make the merry go ’round, so to speak. Michael quickly learned that the guide had not been kidding when she warned riders that the carousel could reach very high speeds, and that if their feet slipped off the pedals, they should lift them out of the way to avoid bodily harm because the pedals would continue to spin at an alarming rate. The games we enjoyed most were the fairground installations in which players tossed balls into a set of holes, which then moved either their respective race horses along a track, or their tray-carrying waiters to customers across a café. We got to try the horse race; Michael’s steed was the victor in his group of twelve contestants; Nancy got a turn in the next group and was happy that her horse at least “showed.”

One can reserve various areas of the Musée des Arts Forains for private events. If you live in Paris, we recommend it as a unique place to host a birthday, graduation, or anniversary party. If you’re visiting Paris (and especially if you’re visiting Paris with kids), we recommend it as a fun departure from the city’s better-known museums. Although the tour was given only in French, our guide was easy to understand because she employed a lot of animated body language.

Welcome sign |

Pavillons de Bercy from the street |

The tree-filled courtyard inside the gates |

Mechanical horse race game |

Winning is a function of getting more balls into the higher valued holes |

A more Parisian-style race: waiters serving customers |

A carousel horse with the head of Âli Pasha, grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire and ambassador to England and France in the mid-19th century, with our excellent guide |

Victor Hugo rendered in wax at different stages of his life |

Crusader Louis IX (St. Louis) rendered in wood |

Wooden calliope |

Nancy on a merry-go-round |

Michael on a merry-go-round powered by cycling riders |

Ball toss game |

Shuffleboard game with a Moulin Rouge theme |

A stationary “hot air” balloon |

Theatre for talking mannequins |

Cour Saint-Émilion in Bercy Village—a collection of boutiques and cafés occupying former wine warehouses |

Artwork at Notre-Dame-de-la-Nativité à Bercy de Paris, the local parish church |

Musée des Égouts de Paris (Museum of the Paris Sewers)

The Musée des Égouts de Paris (Museum of the Paris Sewers) is both one of the city’s better-known museums and a departure from the ordinary. Most people try not to think too much about what happens to all the solid waste a city with thousands and thousands of residents can generate every day; we just flush our toilets and run our garbage disposals and all the gunk just disappears down the drain. On those rare occasions when we do think about it, we understand that the gunk goes into the sewer system, and that from there, it gets filtered and treated (hopefully) before being released back into the environment. Maybe we’ve even seen pictures of waste treatment plants so we have at least a vague idea of how the process works in modern times. But how did a city with a large population like Paris deal with the problem of human waste hundreds of years ago? And how has waste management evolved over the centuries? These are questions the Musée des Égouts de Paris attempts to answer.

Paris’s first underground sewer was built in 1370, when Paris had a population of about 200,000—the largest of any city in the Western world at the time. The idea of using underground pipes to manage waste was hardly new (evidence of underground sewage systems built as early as 4000 B.C. has been found in Mesopotamia) and Paris didn’t necessarily have the world’s best sewer system in the Middle Ages—nor does it have the best now. But what makes les Égouts de Paris special is that Paris was the first city to offer public tours of its subterranean wastewater canals—thanks to a nudge from Victor Hugo. The scenes that play out under the streets of Paris in Hugo’s Les Misérables not only captured readers’ imaginations, but inspired their curiosity to see for themselves what was down there. The city thus began allowing visitors to the sewers in 1867, only five years after the book’s publication; twenty years later, by popular demand, they were offering guided tours.

Since 2021, the tours have become self-guided, and they’re not terribly user-friendly because the route is not clearly marked and the interpretive panels are not always presented in a logical order. The problem for us was exacerbated by the fact that the English translation provided came in the form of a looseleaf notebook in which the leaves were indeed loose—not to mention unnumbered and out of order. As a result, we’re still not exactly sure how the history of Paris’s waste management system unfolded; however, we did learn that by 1914, more than two-thirds of the city’s buildings had indoor plumbing and were connected to the sewer system, and that in 1935, a plan for treating the sewage rather than simply moving it out ot the city began to be implemented. We also saw a lot of intriguing machinery illustrating the aphorism that necessity is the mother of invention. And yes, the sewers do emit a somewhat unpleasant odor, but after the first ten or fifteen minutes underground you don’t notice it anymore—at least not until you re-emerge into the fresh air outside the museum.

Sewer pipes under the city |

Tunnels are identified by the same names as corresponding streets on the surface |

Protective gear for modern-day sewer workers |

Barges used to dredge the sewers in the past |

Iron balls pushed solid waste through the channels |

This drain cleaner was called a “machine gun” because the fast-moving water throws pebbles and bits of cast iron against the machine like bullets |

Pont Alexandre III, a monument honoring the Marquis de Lafayette (center), and the Grand Palais |

Since 1856, this statue of a Zouave (a French-Algerian soldier) under the Pont de l’Alma has been used as an informal measure of the river’s water level |

The Seine from the Pont de l’Alma |

Nicholas Flamel House

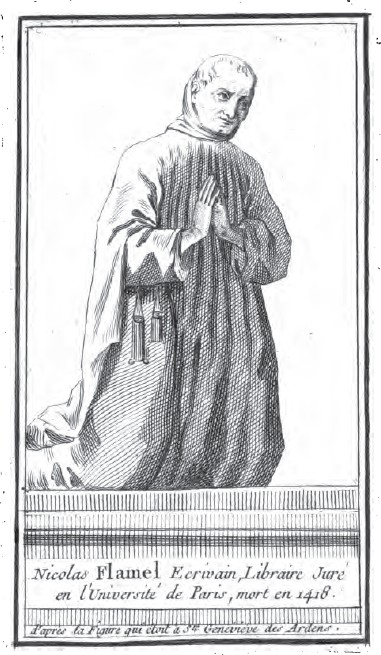

If you were like us, you thought Nicholas Flamel sprang from the mind of J.K. Rowling as the creator of the Philosopher’s Stone, the magical mineral that He Who Must Not Be Named wanted so desperately to obtain. If you were like us, you thought Michael Scott’s fantasy series, The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel, was based on that reference in the first Harry Potter book. And if you were like us, you would be wrong. It turns out that among the scores of wizards, witches, muggles, and other creatures Rowling conjured up for her fantasy series, Nicholas Flamel is the only one who is an actual historical figure. We discovered this when we learned that the oldest domestic residence in Paris had been built by Nicolas Flamel (no h in the French spelling), a well-to-do medieval scribe and bookseller whose wealth increased considerably when he married a rich widow. Flamel was also reputed to be an alchemist, a scientist-philosopher who hoped to discover how to transform ordinary metal into gold. But creating gold from dross was only one step toward the alchemist’s ultimate goal: discovering or developing a substance that could cure any disease and grant immortality.

According to legend, Nicolas Flamel either found or created the Philosopher’s Stone and did indeed become immortal—despite the fact that French church records indicate that he died in 1418 while in his eighties, and was buried in the Church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie. Flamel’s gravestone can be seen at the Musée de Cluny; we did not go to see it, but we did visit the house he built in the rue de Montmorency in 1407. This was not his own residence, but one he built as a shelter for homeless workers, in memory of his deceased wife, Perenelle. An inscription on the wall indicates that residents were required to repent and pray daily for the grace of God, so maybe we should be remembering Nicolas Flamel as a pious philanthropist rather than as an alchemist bent on achieving immortality. Either way, it seems that he succeeded in living on in the world’s memory.

Today the building houses a restaurant and a private residence, neither of which a homeless worker could afford.

Nicolas Flamel House |

A representation of the Good Samaritan above the French philanthropist’s initial |

Nicolas Flamel |

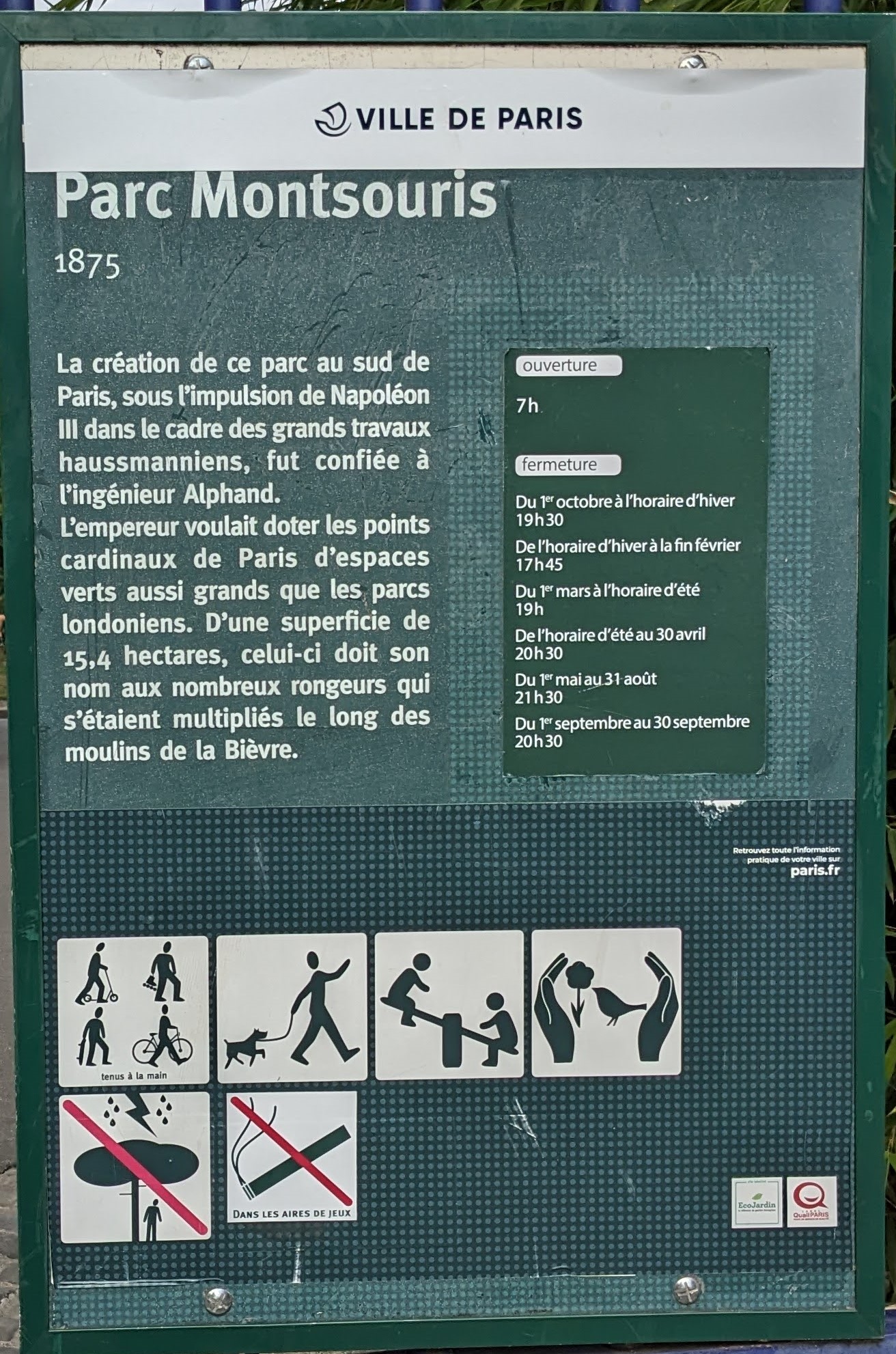

Parc Montsouris

As Paris became more urbanized in the nineteenth century, Napoleon III charged the local prefect, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, to preserve some green space within each quarter of the city. This was accomplished by creating four large parks, similar to the public gardens and recreation areas established in other major cities around the globe. The four in Paris include Bois de Vincennes on the east side, Bois de Boulogne on the west, Parc des Buttes Chaumonts on the north, and Parc Montsouris on the south. Parc Montsouri, which opened in 1875, is the smallest of the four, comprising 15.5 hectares (about 37 acres. For comparison: New York’s Central Park covers 843 acres). It was designed in the “English” style, meaning that its features are meant to look natural rather than formal and symmetrical.

The site that became Parc Montsouris seemed ill-suited for a “natural” public garden. First, the Petite Ceinture (Little Belt), the rail line that encircled Paris at the time, ran right through the property, most of which had been a stone quarry and was completely devoid of vegetation. Another point on the minus side was that under the stone quarry was a system of tunnels from a long-abandoned mine, and the tunnels had become one of Paris’s famous catacombs. About six hundred human skeletons had to be removed and relocated before construction on Parc Montsouri could begin. Nevertheless, the park-planners persisted, creating a natural-looking landscape with a man-made lake and waterfall, wooded hills, and broad lawns. It also has a café, a weather station, and a puppet theatre.

Welcome sign |

Parc Montsouris map |

Parc Montsouris |

Here we should note that a visit to the catacombs was high on our list of new things to do in Paris. However, tours can be booked only a week in advance, and because we were distracted by our travels the previous week, by the time we remembered to try to reserve tickets for the catacombs, there weren’t any left. 😟

Père Lachaise Cemetery

Even though we missed our chance to visit the catacombs on this trip, we still had an opportunity to inspect tombs and pay our respects to the dead at the Cimetière du Père Lachaise, the largest cemetery in Paris. It was named for Louis XIV’s confessor, who lived in the Jesuit house that once stood on the site of the cemetery’s chapel. Technically, this was a “new discovery” only for Michael because Nancy had visited a couple of times during previous sojourns in Paris. (We’re not sure why Nancy had been and Michael hadn’t; maybe because Nancy has always been more interested in the macabre than Michael.) But Père Lachaise is not just any old graveyard; it is the final resting place of many, many people whose names you would recognize—and many, many, many more whose names few would recognize. According to local records, more than a million people have been buried in Père Lachaise since it opened in 1804; the remains of perhaps two million more are stored in a huge ossuary behind a monument dedicated simply “To the Dead” (Aux Morts). The tombs and monuments are crammed so tightly together in the 110-acre (44-hectare) graveyard that it’s hard to believe they could find room to bury anyone else, but Père Lachaise is still accepting the remains of the recently deceased—if they die in Paris, and if the family already has a plot or a vault where they can be placed. Open vault space does occasionally become available, but the waiting list is long. As in most other European countries, gravesites here are regularly recycled because land is scarce, and people just keep dying.

We didn’t have a lot of time to spend in Père Lachaise, so we obtained a map indicating where the tombs of famous people are located and tried to see as many as we could while we made our way across the cemetery. Even with the map, individual graves were not always easy to spot; it was like trying to find Waldo, dressed in gray sweats instead of his signature red-and-white stripes, in a museum full of marble statues.

The whole of Père Lachaise cemetery is crowded with tombs |

A ossuary containing the bones of perhaps 2,000,000 people lies behind a monument to the unnamed dead |

Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850), novelist and playwright |

Georges Bizet (1838-1875) composed Carmen and other operas |

Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849), composer and pianist |

Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), painter |

Georges Seurat (1858-1891), pointillist painter, is buried in the family tomb |

Honoring the Parisian dead of “The Great War” |

On the western wall of Père Lachaise hangs a plaque almost a thousand feet long, inscribed with the names of over 94,000 Parisians who were killed during World War I |

Petite Ceinture (Little Belt)

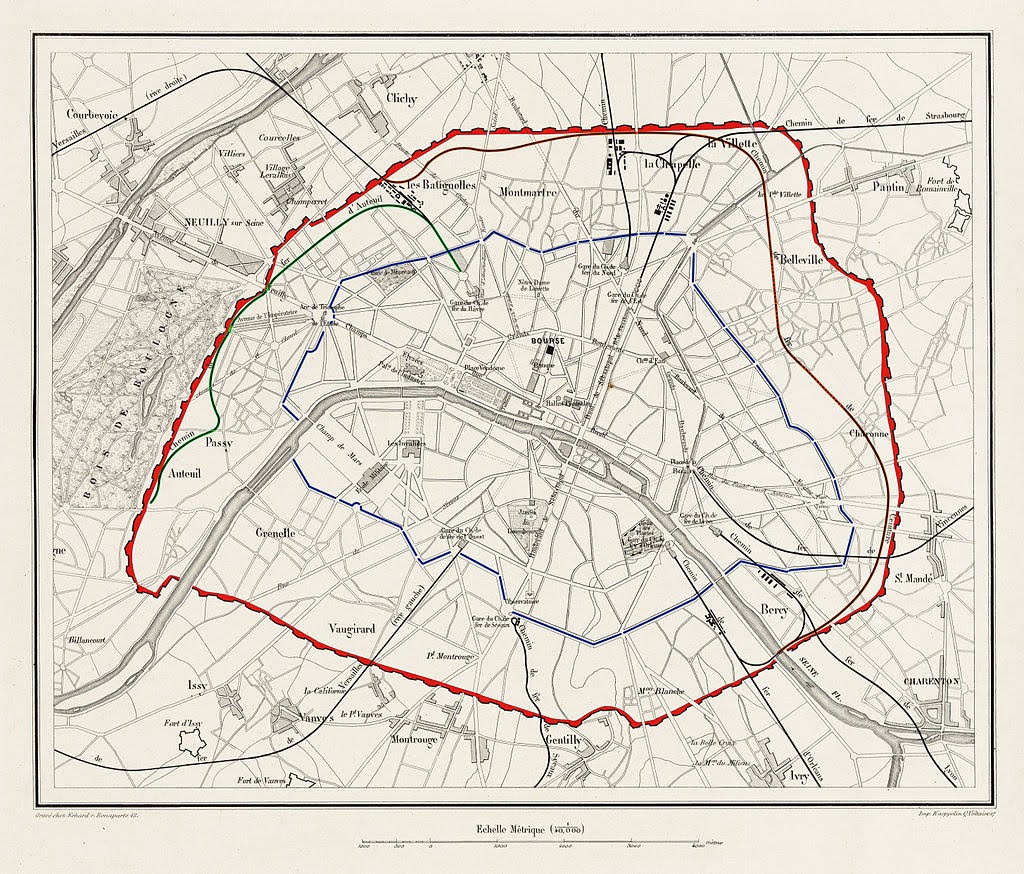

The small-gauge railway that ran through the site of Parc Montsouris was built between 1834 and 1867. Unlike the other rail lines already serving Paris, the Petite Ceinture was state-owned, designed and built by the military to expedite the transport of arms and personnel between the other routes, which were operated by five different private companies. Soon, the Petite Ceinture also began carrying regular passengers, and was especially useful when visitors poured into Paris to attend the Exposition Universelle (aka World’s Fair) in 1889. The route of the Petite Ceinture hewed fairly closely to the Enceinte de Thiers, a fortification wall built during the 1840s to protect the city from invasion. Neither the wall nor the railway exists in its original form anymore. The wall was dismantled after World War I, when it became apparent that old-fashioned stone fortifications wouldn’t offer much protection against modern weaponry. Likewise, the need for the Petite Ceinture diminished when the underground Metro system was built during the first decades of the twentieth century.

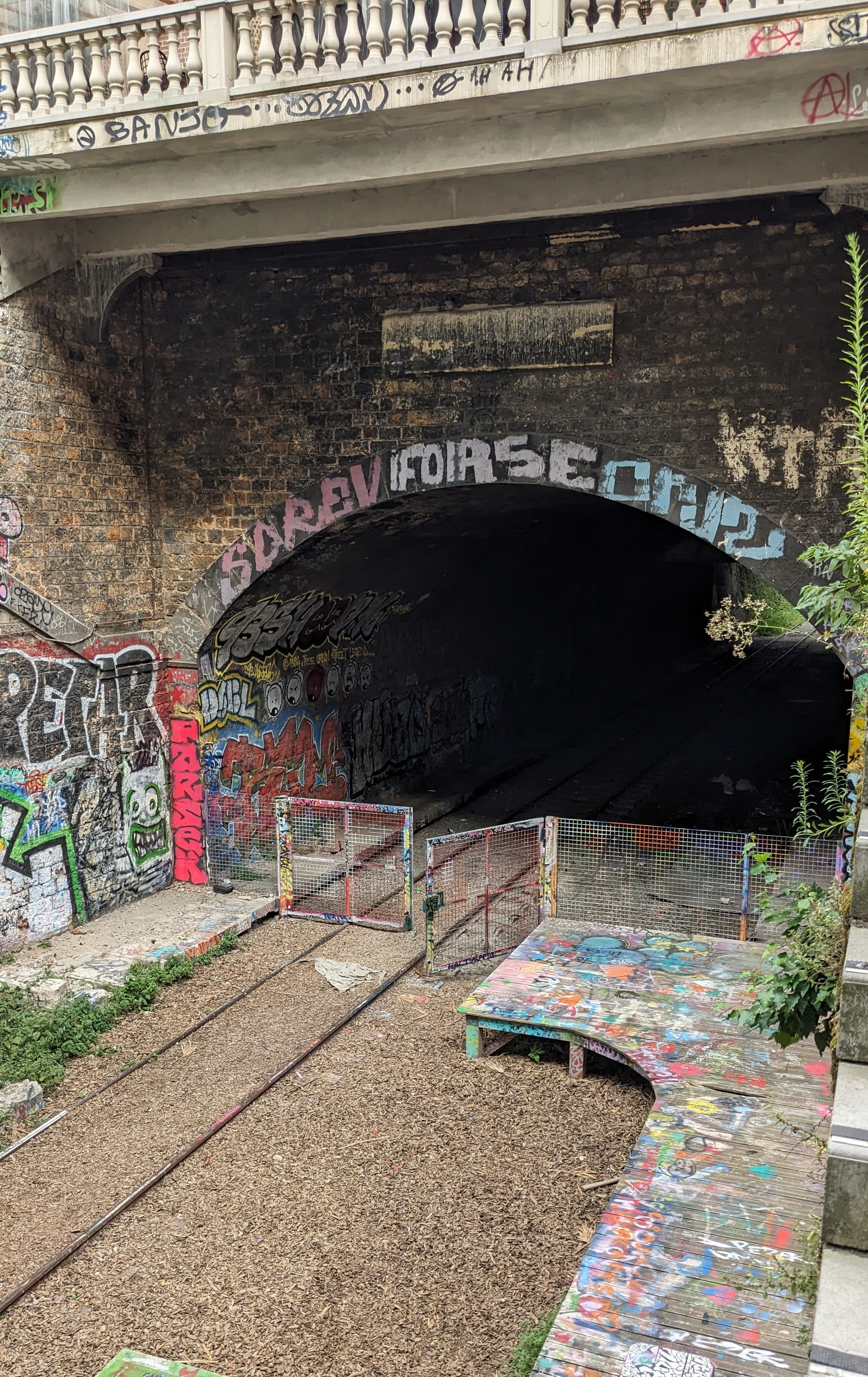

Today, vestiges of the Petite Ceinture still encircle Paris, most just outside the périphérique (ring road) that defines the city’s traditional boundaries in about the same place the Enceinte de Thiers once did. Apparently, it’s still possible to circumnavigate the old rail route on foot, passing through some public gardens and playgrounds; most stretches, however, are simply abandoned tracks and tunnels. We took a look at a tunnel that runs under the avenue du Général Leclerc near the Porte d’Orleans, but even though the gate was open, we decided not to venture into the darkness.

Map of the Petite Ceinture (in blue) |

A vestige of the Petite Ceinture railway |

Stairs from the avenue du Général Leclerc to a segment of the Petite Ceinture |

Promenade Plantée René-Dumont

Much more inviting than the stretch of the Petite Ceinture we encountered was a stretch of the Promenade Plantée René-Dumont (René Dumont Planted Walkway). Also known as the Coulée Verte René-Dumont (René Dumont Green Belt), the long, narrow park follows the defunct Vincennes railway line through the 12th Arrondissement, crossing its elevated viaducts as well as its ground-level sections. Named for an agronomist who was an early promoter of sustainable environmental policies and practices, the Promenade Plantée opened in 1993, becoming the world’s first elevated park. (And according to some, it’s “way better” than New York City’s High Line, a similar greenway developed on a former rail line about 2009.) We wished we had had time to traverse the whole 3-mile (4.7 km) route.

Sculpture on the Promenade plantée René-Dumont |

Promenade plantée René-Dumont |

Promenade plantée René-Dumont includes some fitness stations |

59 Rivoli

In 1999, long after the Second Empire-era building at 59 rue de Rivoli had been abandoned by Crédit Lyonnais and the city had sealed its entrance with concrete to prevent drug addicts and other squatters from using it, a group of avante-garde artists tore the place open and claimed it as their own. They set up studios and galleries, and before long were hosting exhibitions and performances there. Word got around. By 2001, nearly 100,000 curious art-lovers had visited 59 Rivoli, despite the fact that its artist-occupants still had no legal right to be there. In 2006, recognizing that 59 Rivoli had become one of Paris’s most popular contemporary art attractions, city administrators decided to commandeer the building so they could at least bring it up to code. After the necessary renovations were completed in 2009, the six-story walk-up reopened, providing low-cost studio space for more than thirty artists and a unique Paris experience for thousands of visitors every year.

The place still looks like a ramshackle old building, but every surface—inside and out—practically explodes with colorful images. As at its Cincinnati counterpart, the Pendleton Arts Center, the quality of the artwork at 59 Rivoli is as varied as the styles represented. We didn’t see anything we wanted to take home and hang on our living room wall, but it was fun to look around and see what imaginative French creatives have been working on lately.

59 Rivoli was closed when we first arrived, so we returned later |

The art center at 59 Rivoli is a place to see and be seen |

A “view of Paris” in the stairwell at 59 Rivoli |

An unnamed sculpture |

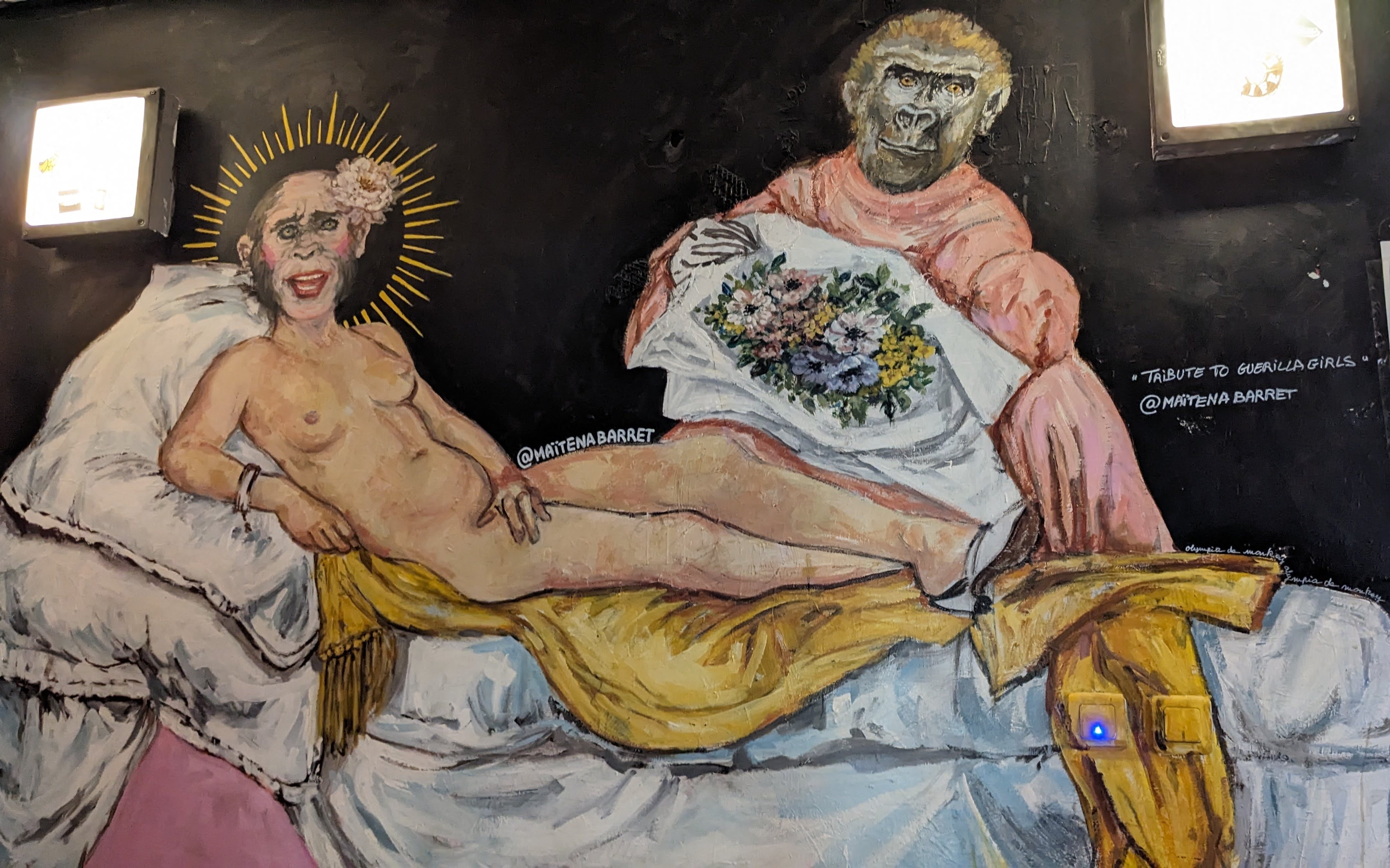

Manet’s Olympia, which we had seen at the Musée d’Orsay . . . |

. . . and “A Salute to Gorilla Girls” by Maitena Barret at 59 Rivoli |

Stohrer Pâtisserie

When we took the bread-baking class at Le Petit Mitron earlier in our trip, we learned that croissants originated not in France, but in Eastern Europe. Later, we learned that the same is true of other types of “French” pastries. So why do those fancy, sinfully rich baked goods seem so quintessentially French? Here’s the history:

In 1725, Louis XV of France married Marie Leszczynska, a Polish princess who had been living in exile in Alsace-Lorraine. Part of the retinue Marie brought with her to the Palais Royal in Paris was her father’s pastry chef, a German named Nicolas Stohrer. Stohrer thus became the pastry chef for the household of Louis XV. Apparently, the position did not preclude any side hustles, because in 1730, Stohrer set up his own pâtisserie in the rue Montorgueil. Unlike other pâtissiers of the time, however, he did not simply make pies; he made all manner of sweet treats: pies, tarts, cakes, waffles, brioches, cream-filled pastries, and more. One specialty he is credited with is baba au rhum, a yeast-raised bread soaked in rum. Stohrer is said to have invented this confection when Marie’s father, the exiled king of Poland, insisted on eating a dried-out currant bun even though it was hard for him to chew. Stohrer soaked the bun in sweet wine, which proved to be a highly satisfactory solution; baba au rhum became one of the most popular offerings at Stohrer’s shop. Another Stohrer creation is the religieuse, two chocolate-frosted cream-filled pastry puffs stacked atop each other to resemble a plump little nun—an example of the creative flair with which Stohrer presented all his bakery items. Probably more than anyone else, Nicolas Stohrer is responsible for transforming pastry-making into the artform that made French pastries the pinnacle of the baking world.

Pâtisserie Stohrer is still open at its original location at 51 rue Montorgueil—the oldest pastry shop in Paris. It’s not very big, and on the day we visited it was even more crowded than the Manet-Degas exhibit at the Musée d’Orsay, so it was hard to get a good look at the edible artworks in the display cases. We can’t tell you whether they tasted as good as they looked because we were disinclined to pay premium prices just to say we had tried a Stohrer pastry. Plenty of other Parisian pâtisseries have mastered the art of fine baking since 1730, so we decided to look for less expensive treats elsewhere.

Stohrer, the oldest pâtisserie in Paris |

Baba au rhum (center, almost gone) and other works of the pâtissier’s art |

Macarons and éclaires |

What’s next?

Here are some places we would like to see on future visits to Paris:

- Catacombs

- Musée Curie (formerly the Radium Institute, Marie Curie’s office and laboratory)

- Musée Edith Piaf (the singer’s personal apartment)

- Musée Nissim de Camondo (18th century decorative arts collected by a wealthy Jewish family with a tragic history)

What are your favorite places in Paris? What have we missed that you would recommend?

Loved the boat ride on the Seine (also at sunset). Musee Rodin was worth seeing, also the museum with all the Matisses. I went to Ladure (sorry, no diacritical marks available in this comment) and was so overwhelmed by all the confections and that I was at the famous Ladure that I couldn’t choose and went off without buying anything. I discovered the best Chinese restaurant in Paris, somewhere between the Fontaine des Innocentes and the Louvre, where I ate lunch often during my five weeks there. I loved the Musee Cluny, as I am fond of medieval things–also all the great places you revisited–Musee d’Orsay, Notre Dame, Sainte Chappelle, all the bridges on the Seine. The china museum in Sevres was worth seeing. I even came to love the sound of near-constant skateboarding at the Fontaine des Innocentes outside my apartment.

Amazing photos and the trip of a life time for you two! Miss you both!!!